RESEARCH LOG

To become an Abstraction

Malevich and the suprematist funeral ritual

by Katerina Sidorova

Malevich and the suprematist funeral ritual

by Katerina Sidorova

March 26, 2024

Artist, scholar, and current research fellow Katerina Sidorova conducts in-depth research on the Khardziev archive. In the research logs she writes for Stedelijk Studies, she addresses various topics related to the avant-garde movement of the early twentieth century. In this third research log, Sidorova reconstructs Malevich’s suprematist burial ritual.

“Neither Life nor Death should remain because these two phenomena do not exist apart.”

Kazimir Malevich, “Notes of different years”

What is it like to achieve “supreme” abstraction? To detach from materiality completely and become a mere idea, pure form, pure color? Is abstraction achievable beyond the borders of a canvas, in actuality, within one’s own life or beyond it?

I’m glancing at some photographs. Here’s an image of a sick and bedridden Kazimir Malevich. Here are some photographs of his body in an architecton[1]-shaped coffin, surrounded by his works. Images from a funeral procession in May 1935. A photograph of his family under an oak tree beside a cubic gravestone marked with the infamous black square, again dated 1935, place: Nemchinovka.

Ivan Vasilevich Klyun, Kazimir Malevich a Few Days Before his Death, 1935, chalk lithography, 26.7 × 22.5 cm. On loan from the Khardzhiev-Chaga Cultural Centre Foundation. © Foundation Khardzhiev / Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

At the burial site of Kazimir Malevich, © Foundation Khardzhiev.

Kazimir Malevich Funeral, © Foundation Khardzhiev.

Kazimir Malevich, © Foundation Khardzhiev.

Kazimir Malevich Funeral, © Foundation Khardzhiev.

Kazimir Malevich Funeral, © Foundation Khardzhiev.

Kazimir Malevich Funeral, © Foundation Khardzhiev.

Ivan Vasilevich Klyun, Malevich a Day after his Death, 1935, colored pencil and gouache on paper, 16.5 × 15.5 cm. On loan from the Khardzhiev-Chaga Cultural Centre Foundation. © Foundation Khardzhiev / Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Kazimir Malevich Funeral, © Foundation Khardzhiev.

The architecton coffin of K. Malevich, made according to the design of Nikolai Suetin © Wikimedia Commons.

Lenin Mausoleum, Moscow © Wikimedia Commons.

Nemchinovka was a small village near Moscow, and the place where Kazimir Malevich was buried. However, anyone visiting the area now would find neither oak tree nor gravestone nor even the field in which these were located. In fact, Nemchinovka itself no longer exists. That place has disappeared in the midst of time, lost its physicality, giving way to the expanding city of Moscow and its streets and buildings. Gone is the village, the field, the oak, the gravestone. Gone are the remains of Kazimir Malevich. All that’s left is abstraction.

To fully understand how Malevich saw his own death, as a historical figure and an artist, let’s retrace his final days and recollections of his close friends and colleagues. “Rites occupied a rather large place in Malevich’s life, despite the fact that he did not talk about them until he was near the end of his life,” writes Ksenia Buksha. Over the course of the decades preceding this, his vision of a “good death” had been shaped by personal experience of loss and grief and informed by philosophers such as Nikolai Fedorov and figures like Helena Blavatsky and Daniil Kharms.

On November 7, 1918, Olga Rozanova, a dear friend and fellow avant-garde artist, died of pneumonia in Moscow, Russia. As far as I have been able to determine, her funeral was the first ever suprematist farewell parade, small in scale and intimate, yet containing the elements of what could later be described as a “suprematist funeral.” Leading the funeral procession, Kazimir Malevich, who was involved in the mortuary preparations, carried a black banner featuring a white square.

Six years later, Malevich took part in the funeral of and memorial service for Vladimir Lenin, following his death on January 21, 1924. The passing of the first Soviet leader and face of the proletarian revolution prompted discussion on how best to commemorate his legacy. At the time, Malevich was a prominent figure in the avant-garde movement, and his artistic contributions were highly valued by key figures in the early Soviet state. It was Malevich who suggested creating a cult of Lenin featuring musical and poetic pieces honoring the leader.

Every Leninist was to have a cube at home, according to Malevich, to remind them of the continuous, long-lasting lesson of Leninism. Additionally, Lenin corners were to be set up across the USSR. Like the pyramids in Egypt, the cube would symbolize the main aspect of the cult: eternity. Lenin’s body was to be placed in a structure that contained a passage to the cube.

Shortly after Lenin’s death, Malevich wrote on this subject: “The point of view that Lenin’s death is not death, that he is alive and eternal, is symbolized by a new object that takes the form of a cube. The cube is no longer a geometric figure. This is a new object through which we are trying to depict eternity, create a new set of circumstances—and with them support the eternal life of Lenin, conquering death.”

And indeed, shortly afterwards, architect Alexey Shchusev was entrusted with the honorable task of designing a tomb for the leader. He presented a drawing of a structure composed of three horizontally arranged cubic volumes.

Finally, in 1929, the untimely passing of Ilya Chashnik, one of the two foremost disciples of Kazimir Malevich, gave rise to the first complete suprematist funeral rite involving a white cube. Chashnik’s funeral included a special suprematist ritual developed by Malevich himself. A white cube with a black square was installed on the grave, which bore the inscription: “The world as non-objectivity.”

As for Malevich’s own post-life wishes, sources often contradict each other regarding the extent to which the theme of his own mortality arose in personal and professional conversations. In the last years of his life, Kazimir Malevich did speak about his death and the burial rituals he expected to follow the event Even before his final illness, he told his wife and the artist Ivan Klyun that he wanted to be buried in a location between Barvikha and Nemchinovka. He even invited Klyun to be buried beside him.

“Klyun recalls an elegiac conversation between them in 1933, in which Malevich told him that this would be their last walk together” (he was not yet sick), writes Ksenia Buksha. “Klyun objected to Malevich’s plan because Barvikha and the entire bank of the river had been declared off-limits by that time, as it was to be the site of a sanatorium for the Council of Ministers. Then Malevich pointed to the very oak under which he wished to lie.”

In December 1933, the already ill Kazimir Malevich wrote his will:

“I ask to cremate my body in Moscow, do not refuse me this. Klyun and my brother artist Suetin, may build a column according to his (Suetin’s) model, in which there will be an empty urn.”

“A column is a vertical architecton, and an empty urn means without ashes, without an object, without itself. In essence, this is not a grave, but a memorial, a monument to the spirit,” Ksenia Buksha explains in her book about Malevich: “There were no other testaments and instructions from Malevich on the funeral script and the shape of the coffin.”

More evidence of Malevich sharing his views on dying and burial rituals is provided by his student Konstantin Rozhdestvensky. According to Malevich, the deceased had to lie with his arms outstretched, face up—as though embracing the sky, the universe and assuming the form of a cross. According to this vision shared in a letter to Klyun, a giant architecton would be installed on the artist’s grave: “a tower in the shape of that column (his 1927 Suprematist Architectural Model) in the Tretyakov Gallery, with a tower in which a Jupiter telescope will be placed.”

These recollections can be linked to the influence of cosmist philosophy and theosophy on the work of Malevich and the concept of suprematism specifically. Cosmism is a philosophical movement based on a holistic worldview. It is characterized by the awareness of universal interdependence, unity, the search for man’s place in the cosmos, the relationship of space and terrestrial processes, the recognition of the proportionality of the microcosm (man) and the macrocosm (the universe), and the need to measure human activity by the principles of the integrity of this world. Cosmist philosophers like Nikolai Fedorov aimed to overcome death, overcome its physicality and guarantee immortality for all.

Sadly, the final years of Malevich’s life were spent in a futile battle with cancer. Possibly unaware of the seriousness of his disease (some sources speculate that the diagnosis was hidden from the artist by his family), he, largely bedridden, spent his days in hopes of recovery and making glorious plans for the future, clinging to life and refusing to let go of its physicality.

Kazimir Malevich died in Leningrad on May 15, 1935.

Contrary to popular belief, Malevich did not design the coffin in which he was buried. However, this legend is not entirely without foundation. After Malevich’s death, his pupils Konstantin Rozhdestvensky and Nikolai Suetin designed a coffin and presented illustrations to a carpenter. The illustrations showed a green, black and white coffin with a red circle at the feet and a black square at the head. They excluded the sign of a cross to avoid any references to religion.

“Thus began the funeral of the Suprematist—not Malevich’s last, posthumous masterpiece, as many believe, but the feat of his faithful students, who understood how important the new suprematist ritual was for their mentor, who had devoted much thought to it in the latter part of his life.”

The civil memorial service was held in the artist’s apartment. The death mask was taken and the body embalmed, then moved to a large living room where paintings were hung on the walls by friends and family. The coffin was placed with its head toward the “Black Square,” next to the coffin – an unfinished painting, a palette with brushes and paint, a photograph of the deceased was pinned to the frame. On May 18, Malevich’s body was removed from the room for its journey to Moscow. The reinforced coffin was placed on a truck covered with red cloth, the sides of the vehicle open to allow onlookers see the closed coffin. Suetin had painted the truck in suprematist style, in the colors of red, black and green. Attached to the front bumper was “The Black Square”. The coffin was unloaded at the train station and placed in a freight car for transport to Moscow. A black square was painted on the side of the freight car.

After cremation, the artist’s ashes were placed in an urn and buried in Nemchinovka on May 21. A wooden cube made by Suetin and featuring a black square on one of its sides was installed on the grave. A board was nailed to the oak with the words: “The ashes of the great artist K.S. Malevich (1878-1935).” Wreaths were hung from the branches of the old tree that Malevich himself had chosen as his final resting place.

Shortly thereafter, the cube began to collapse. Plans to erect a monument according to Suetin’s project (column-architecton) have never been fulfilled. Then war broke out. The oak served as a notification point for German air raids on Moscow. Once, while playing under the oak tree, some village children dug up the urn with Malevich’s ashes and broke it open, but found nothing of value. In 1942, lightning struck the oak and set it alight, but its burnt remnants remained in place until the 1960s. Readers already know how this story ends. There’s nothing left of Nemchinovka, no fields, no oak, no gravestone, no artist remains. Pure immateriality. Pure abstraction. Abstraction in the supreme.

Malevich believed that the new society should have new burial rituals. He believed in abstraction as a way of transformation. The rite of the final passage of the future had to be a suprematist funeral: open, embracing of the universe, aligned with cosmic rhythms. His own funeral and the destiny of his remains have reflected this new method of dying.

The findings in the Khardzhiev archive reveal not only the visual narrative of Malevich’s burial, but also the conceptual depth of his suprematist ideas on the perception of mortality and on artistic expression and abstraction as a method of overcoming mortality.

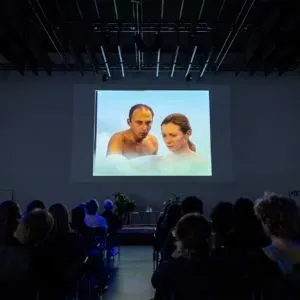

Documentary video from the exhibition Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant-Garde that took place at the Stedelijk from 19 October 2013 until 2 February 2014.

Katerina Sidorova is a visual artist and researcher. She obtained a BFA from both the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, and Yaroslavl State Pedagogical University, Russia after which she traveled to the Glasgow School of Art for a Master in Fine Arts followed by a PhD in Philosophy of Culture at YSPU. Her practice focuses on the absurdity of human existence through its relationships with death, non-human species, societal hierarchies, necropolitics and performativity as a societal political strategy. She is a research fellow at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, where she is exploring Khardziev’s archive of material relating to avant-garde movements that developed at the start of the 20th century in what are now post-Soviet states.

[1] A sculptural and architectural design that solved the problems of Suprematist form-building and operated with architectural categories: mass, volume, tectonics, scale.

Through the Roar of Cosmic Cataclysms

Through the Roar of Cosmic Cataclysms