A Transnational Socialist Solidarity

Chittaprosad’s Prague Connection

Simone Wille

The Indian artist Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (1915–1978) is best known for his visual reportages on the Bengal famine in 1943–1944. As a member of the Communist Party of India (CPI), Chittaprosad’s historic documents of the famine, in the form of sketches, texts and linocuts, were produced in line with the party’s demand for revolutionary popular art to mobilize the masses by means of posters as well as journalistic and documentary-style reports. Many of these works were published in the communist journals People’s War and People’s Age. This is how they circulated among intellectuals and a general readership.

Chittaprosad can be situated within a socially responsive practice that is distinctive for one line of development characteristic of his native Bengal, notably represented by artists such as Zainul Abedin (1914–1976) and Somnath Hore (1921–2006). While these artists have produced compelling images in response to political crisis, the Bengal famine, and peasant rebellions, Chittaprosad’s recognition and fame gained in pre-partition India—unlike that of Abedin and Hore—was not carried into the post-partition era. His dissociation from the CPI in 1948, along with the general atmosphere in postcolonial India, with its concerns for signatures of national-modern art, left little room for a former party artist. This, I will argue, instigated him to build on a network beyond the national frame. The group of individuals from Prague that became aware of and interested in Chittaprosad around that time actively supported his career from this point on. This is how his work increasingly circulated within a transnational network that was marked by solidarity with a socialist outlook and paired with a curiosity for traditional and folk arts. These very personal connections exceeded his lifetime, and most of the documents, book illustrations, poems, and artworks related to this have not yet been studied or published.

This article will reflect on these connections and focus on individuals, such as the assistant to the trade commissioner of Czechoslovakia in Bombay (today Mumbai), with whose help and friendship Chittaprosad was able to establish his puppet theater in the 1950s in the suburbs of Bombay.[1] It will delve into the collection of linocuts, acquired from the artist by the National Gallery Prague in the early 1960s, and it will reference the film made by Pavel Hobl about the artist in 1972. By assessing the contributions that Chittaprosad made to the Czech and English journals Nový Orient/New Orient Bimonthly, published by the Oriental Institute of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, this article will establish an awareness of a transnational network as conceived of spaces, platforms, and institutional and individual support. In an effort to connect with the topic of this journal, it will then elucidate to what extent the circulation and the reception in Czechoslovakia of the works and ideals of the artist Chittaprosad reverberated on his artistic subjectivity in relation to frameworks such as socially committed art, independence and freedom, modernism, and folk traditions. By gathering the multiple threads of histories that seem to have created an alternative space for Chittaprosad, I will investigate how this network and the connections with certain political and cultural geographies of the post-World War II era enabled a geography of aesthetic and emotional solidarity for the artist, and how—without Chittaprosad’s ever having left India—this dialogical field contributed to what Andreas Huyssen has called “alternative geographies of modernism” between the decolonizing and the communist world of the late 1940s up to the late 1970s.[2] Since Chittaprosad has only recently gained attention nationally and internationally as an artist primarily dedicated to the cause of humanity under the impact of political struggle, this article points to the necessity of integrating the topics of mobility and migration in relation to the formation of his work, so that he can then be discussed from the broader framework of modernism as informed by plural sites and plural forms.[3]

The Communist Party of India, the Bengal Famine, and Art for a New Audience

Chittaprosad grew up in Bengal, went to school in Chittagong, in today’s Bangladesh, and started out as a self-taught artist trying out artistic styles that were close to a variety of traditional Indian arts, including sculpture. During World War II, India was heavily involved in war activities as a British colony, and Calcutta (today Kolkata) was “one of the centers of India’s war production.”[4] In the midst of wartime uncertainties and strong anti-colonial political activities, the Japanese attacks along the eastern borders of Bengal, the fall of Rangoon, and the repeated bombing of Chittagong in the early 1940s nurtured wide anti-fascist activism. Chittaprosad witnessed tens of thousands of Burmese refugees come fleeing across the Bengal border, and he began to paint anti-fascist paintings and posters, which he showed at villages in the countryside along the border areas of India and Burma. The peasants and village people of this area were thus, in Chittaprosad’s own words, “the first of a new fresh audience for a new fresh Indian Art.”[5]

Chittaprosad belonged to a generation growing up and living in Chittagong that, according to the artist Somnath Hore, “turned to communism after being disillusioned by the failure of the extremist politics of the early twentieth century.”[6] Chittaprosad’s anti-Japanese posters caught the eye of the general secretary of the Communist Party of India (CPI), Puran Chand Joshi (1907–1980), which is how he came to work in the party’s cultural movement. Chittaprosad was sent to the party’s headquarters in Bombay in the early 1940s and became actively involved with the cultural wing of the CPI, the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), founded in 1943. Communist artists working for the IPTA produced pamphlets to mobilize the masses against fascist forces, colonial rule, feudalism, and industrial capitalism. The relevance and importance of culture as a tool for communicating political struggle to the masses was clear to Joshi, and it was his initiative to send Chittaprosad and the photographer Sunil Janah (1918–2012) to the severely famine-stricken Midnapur district in November 1943, to document the famine.[7] Known as the Bengal famine, it is considered one of the most devastating events of World War II, and was entirely man-made.

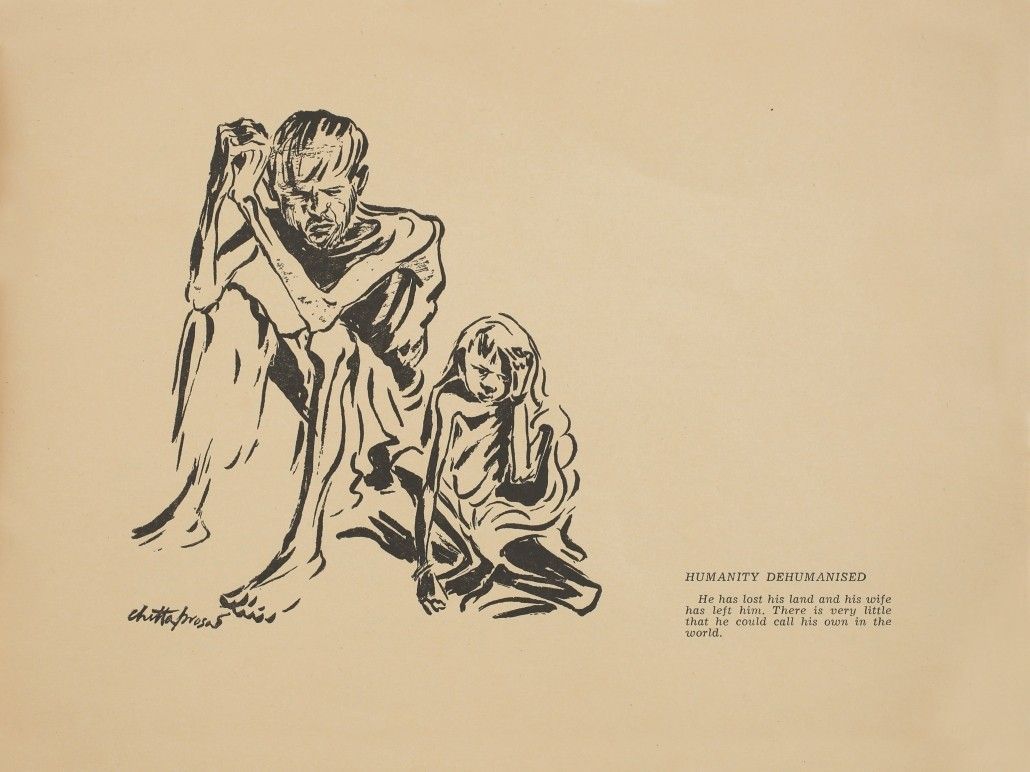

The drawings and sketches along with text were published as a visual reportage of the artist’s direct experience of traveling through the Midnapur district, mainly on foot. A selection of twenty-two sketches was published in the form of a book, titled Hungry Bengal,[8] and other drawings along with text were reproduced in the CPI’s official organ, People’s War and People’s Age, as early as August 1943 (fig. 1).[9] These works were then subject to suppression by the British.[10]

Fig. 1. Chittaprosad, “Humanity Dehumanised,” 1943 from Hungry Bengal. Image courtesy of the Chittaprosad Archives, DAG Archives, New Delhi.

Hungry Bengal and the many other reports by the artist became famously associated with Chittaprosad. The works reflect the artist’s experiences of the life-and-death struggle against the backdrop of the global war and in connection with the Japanese invasion. The famine, in conjunction with its corrupt politics and paired with the hatred for the British as being responsible for all this misery, left a profound mark on Chittaprosad and lastingly defined him as an artist. This is also what defined his moral and political ideals; he understood painting as a weapon, which he came to describe in his own words by saying, “I was forced by circumstances to turn my brush into as sharp a weapon as I could make it.”[11] Executed with black ink and on cheap paper, Hungry Bengal is, above all, marked by the space that the artist gives to the sketchy composition of either single personalities, intimate groups of people, or the many horrific situations that he encountered on his tour, which he paired with his notes, with text, that reflects the very emotional and empathic encounters that the artist made. Thus, against the depiction of an idealized reality, Chittaprosad consciously worked to demonstrate political commitment with social consciousness, along with solidarity through direct contact with the famine victims. Chittaprosad continued to work on the famine, and documented the after-effects. Immediately after the war, he painted propaganda posters that targeted the colonizer, and he documented the armed Telangana movement that started in 1946. After independence, he also began to direct his criticism towards the Americans, in line with the general change of power. One of his iconic cartoons (fig. 2) depicts Jawaharlal Nehru accepting money from the barrel of an American gun while the deprived—represented by a mother with her child—are reaching out for communist help, represented by a colossal hand and fist.

Fig. 2. Chittaprosad, People’s Democratic Front, brush, pen and ink on paper, 1952, 34.8 x 50.8 cm. Courtesy of Osianama Research Center, Archive & Library, India.

The late 1940s is also the time when Chittaprosad responded to the first call of the communist-led world peace movement in an urge, as I would suggest seeing it, to remain socially committed as an artist and at the same time connect with a wider, transnational and progressive cause. The work Call for Peace (fig. 3) was possibly connected to this involvement.[12] This is one of thirty-eight works on paper that were acquired directly from the artist in 1964/65 by the National Gallery Prague.[13]

Fig. 3. Chittaprosad, Call for Peace, 1952, linocut on paper, 30.5 x 29.6 cm. Photo © National Gallery Prague, 2019.

The late 1940s were also marked by a major shift within the CPI. Purand Chand Joshi was ousted after having praised the Indian National Congress for its achievement of independence in 1947. The national coexistence of the party under his leadership, which “did not accept the notion that in colonial countries nationalism was a bourgeois concept and that this concept clashed with internationalism,” was unacceptable to the Cominform (an organization created in 1947 to coordinate international Communist parties).[14] As a consequence, communism among writers, artists, and intellectuals went into decline, and Chittaprosad also distanced himself from the party in 1948.[15] Disillusioned, he went into self-imposed isolation on the outskirts of Bombay, and probably will have welcomed the interest that came to him from Prague.

Prague Connections and Building on Friendly Ties

On December 30, 1950, the Czech Indologist Miloslav Krása wrote a letter to the Indian artist Ram Kumar (1924–2018).[16] Kumar, like many Indian artists, was staying in Paris in the late 1940s and early ’50s, attending art lessons with both André Lhote and Fernand Léger.[17] According to Krása’s letter, Kumar had come to visit Prague, and there is said to have shared his literary and painterly work. Krása, in this letter, reminds Kumar to not forget to help him find out more about the “Indian cartoonist Chittaprasad [sic],” of whom he has just been able to see “some very impressive linocuts” in “a new issue of a Bengali Literary Magazine.”[18] Krása does not inform us in which Bengali literary magazine he saw Chittaprosad’s work, nor does he inform us what kind of work he saw. Since he is referring to a new magazine, he most likely saw new works by Chittaprosad, who, by the late 1940s, had turned away from a “strictly partisan political affiliation” with the CPI, to widen his scope towards broader social concerns that included the world peace movement.[19] While his works throughout his career continuously reflected a concern for the deprived, the poor, and the oppressed with increasing focus on the plight of children, he came to employ an artistic strategy that clearly resisted postwar modernist formalist strategies to a large extent, and instead adhered to a realism whose components were made up of a mix of socialist realism and folk traditions.[20] Sanjukta Sunderason notes that images of socialist realist works from certain parts of the world were available in India via People’s War between 1944 and 1945, featuring examples of Chinese woodcuts along with reports about Chinese peasant resistance.[21] It is therefore very possible that Chittaprosad was aware of such images.

While Chittaprosad’s appropriation of traditional and folk elements reflected the CPI’s awareness of the value of folk traditions as a way to claim one’s cultural space, this also needs to be seen in relation to how Indian modernism from the 1930s onwards has drawn inspiration from folk elements. In this context, Geeta Kapur refers to “the artisanal basis of Gandhian ideology” and elucidates how this “appropriation of the folk as an indigenist project” developed into “a populist modernism.”[22] Kapur carries on by citing the CPI’s mediation of folk traditions towards “progressive” and “clearly socialist ends,” and calls this “an indigenous variant of socialism.”[23] While popular art and folk traditions were appropriated nationally, especially from the 1930s onwards, with Jamini Roy’s (1887–1972) primitivism as a notable representative, the CPI made use of such modalities in more or less functional terms critiquing British colonialism. However, Chittaprosad’s imagery, which increasingly employed a combination of socialist content in an iconographic mix that celebrated and referenced traditional and folk elements, attracted the Indologist Krása’s attention precisely because, I would like to argue, of this iconographic schema.

A 1961 article by Krása in the cultural and political monthly New Orient Bimonthly may well read as a confirmation of this. Here, Krása elaborates on Chittaprosad’s “service and contribution” to Indian art, which he sees in the artist’s “successful struggle for a new content, form, technique and mission for works of art.”[24] Krása sets this apart from “temptations” to “paraphrase Old Indian motifs” via “romanticizing pastel” or “modern western schools and the copying of foreign models,” and he continues by celebrating Chittaprosad for his “art that is national and popular in the best sense of the word.”[25]

Chittaprosad’s progressive imagery thus had all the necessary ingredients for his being assigned as a welcome and regular contributor to Nový Orient and its English-language version, New Orient Bimonthly. Both journals can be seen as publications in which visuals along with text were intended to reflect on the high level of connectivity of Czechoslovakia across a newly morphing world in the postwar era that was marked by the idea of building new societies. As conversations were carried out cross-culturally via the journals, they can be viewed as platforms from which a widely transnational reach of cultural exchange was practiced, and Chittaprosad, whose contributions to the journals seemed to have been a source of income in the financially difficult life of the artist, experienced this “brotherly” solidarity directly.[26]

In a series of letters written by Chittaprosad to Krása between 1958 and 1964, the artist thanks Krása for several payments that he received for his work related to the journals.[27] From these letters we also learn that Chittaprosad received various copies of the journals, along with other material such as a catalogue of Mexican art.[28] The artist comments on this and notes that he has long been fascinated “by the power of the ancient Mexican art [and that he has] been able to collect a few fully illustrated books on this.”[29] While we do not know exactly what Chittaprosad saw in reference to ancient Mexican art, this connects well to an understanding of his work in its revolutionary tone and aesthetic texture, which Krása connected to Goya’s political satires, the lithographs of Käthe Kollwitz, or the works of José Guadalupe Posada and Diego Rivera, but also to Chinese and Japanese woodcuts and Mexican prints.[30]

With an understanding of his works in line with revolutionary art from around the world, his prints were featured many times in Nový Orient and New Orient Bimonthly to accompany a variety of aspects relating to Indian and South Asian cultural topics, such as discussions and translations of literary as well as political themes. Some of his works featured in the magazines also form part of the collection of the National Gallery in Prague, such as the work titled Killed & Wounded! (fig. 4) that appeared in a 1961 volume of Nový Orient next to Czech translations of Indian folk songs.

Fig. 4. Chittaprosad, Killed & Wounded!, date unknown, linocut on paper, 27.5 x 20 cm. Photo © National Gallery Prague, 2019.

The message that Killed & Wounded! conveys is one of protest, where demonstrators are piling up along strong curvilinear lines of soft linoleum behind the front figure, who is lying face down. The determined faces of the crowd are directed towards the audience and convey anger, protest, and determination to carry on with raised sticks. While this is one of many of the artist’s works in defense of the masses that marched against their oppressors and against injustice, within the space of Nový Orient it demonstrates well the sustenance of an exchange mechanism that kept artworks and other cultural forms mobile across the Second and the Third Worlds. The journal’s commitment thereby demonstrated the universal exchangeability of the cause, even if the dissemination of the message was limited to a readership mainly within Czechoslovakia, due to reasons of language.

One of Chittaprosad’s friends who was instrumental in opening up possibilities and enabling the artist’s work to travel to Czechoslovakia was František Salaba. Their mutual passion for theater and puppets is what connected them. Between 1954 and 1957, Salaba worked as an assistant to the trade commissioner of Czechoslovakia in Bombay. He met Chittaprosad at a rehearsal of the Little Ballet Troupe through its founders, Shanti and Gul Bardhan, with whom the artist was friends.[31] Within the framework of IPTA, Chittaprosad had designed panels for theatrical performances that toured India. He had also worked with a group of Rajasthani village puppeteers in Delhi in 1955,[32] and he had designed costumes and screens for the Little Ballet Troupe.[33] While in Bombay, Salaba organized an exhibition of Czech toys and puppets, of which Chittaprosad famously became fond. Salaba then gifted him some puppets and “presented him an entire puppet stage.”[34] This is how Chittaprosad founded Khelaghar, a puppet theater for which he designed the stage and puppets, wrote scripts, and performed plays for the children that lived near his home in Andheri. Chittaprosad acknowledges Salaba in many letters to Krása as one of his best friends, and as the person who was greatly responsible for making “my work famous in your land.”[35]

Chittaprosad’s friends from Prague were hard at work in making connections to boost his career. Many of the Czechoslovaks who came to visit Chittaprosad in Andheri collected works from him and encouraged him in his artistic venture with their committed interest and moral support. Krása, in particular, viewed him as equal to the more celebrated contemporary artists in India, many of whom the Indologist also knew personally. Krása’s effort to thus establish a connection between the successful Indian artist M. F. Husain (1915–2011) and the marginalized Indian artist Chittaprosad must be viewed as a conscious decision by Krása, who might well have seen commonalities between the two. After all, Husain showed his work in Czechoslovakia several times, and his work was also featured in Nový Orient and New Orient Bimonthly along a similar line as the works of Chittaprosad. While Husain’s work in the journal was viewed as both “national” and “international,” it was clearly celebrated for its reminiscence of Indian folk art.[36] The photograph of Chittaprosad animating the Khelaghar puppets in front of his home is from the Krása archive (fig. 5). The artist is in the middle, while Husain is making the puppets move for the children who are sitting, watching the three adult men.

Fig. 5. Photograph by M. Krása, date unknown. As inscribed on the back, we see Chittaprosad in the middle and M. F. Husain on the right. Photo courtesy of Mrs. Helena Bonušová and the Krása family.

By introducing Husain to Chittaprosad, Krása obviously meant well, and not only intended to help the constantly financially troubled artist but perhaps also hoped to enable the disadvantaged artist to find his way into the Indian art scene. Due to several letters exchanged between Růžena Kamath and Chittaprosad, we know that this was a one-time meeting and that it did not turn into a friendship or collaboration of any sort between the two artists. Quite the contrary: it ended up being a huge disappointment on the part of Chittaprosad. In a handwritten, twelve-page letter to Růžena Kamath, dated May 17, 1968, Chittaprosad writes at length about what he feels art should be, and during the course of this monologue he clearly reveals his dislike for Husain, whom he criticizes for having made false promises to him and for being a commercial artist.[37] Kamath, who lived in Bombay, seems to have visited the artist frequently and helped him with a variety of problems—financial, medical, and professional. In the letter mentioned above, the artist explains that he would not be able to attend the celebration of Czechoslovak National Day due to his ill health and his fears of leaving his room, after which he ventures into a more serious explanation about what he thinks and feels about the true meaning of art. This is when he brings up the meeting with Husain, many years previous, initiated by Krása. Chittaprosad complains about Husain’s empty promises of introducing potential buyers to him, and he laments that Husain had only made these promises in the presence of Dr. Krása. Chittaprosad tells Mrs. Kamath that he has never seen any of Mr. Husain’s work and, in fact, says that he has never seen any modern Indian painter’s work. He then confesses to not belonging to “that highly modern aesthetic clans [sic].”[38] While downplaying all modern technical progress, he also denounces art as a commodity by expressing his disrespect for artists who produce art for money, and adds that “art is neither a ‘weapon’ [n]or a means of propaganda of any ideology—as we were told a few years ago by the political pundits.”[39]

Transnational Mobility and Imaginary Geographies

There seems to be a contradictive logic in the above statement—in its denunciation of art as a weapon, as opposed to an earlier statement that declared the potential of art as a weapon—but the artist’s self-imposed isolation after his detachment from the CPI falls clearly in line with it. Yet, what is perhaps more relevant—certainly in the framework of this essay—is the choice that Chittaprosad made in relation to his location, his audience, and his expanded and imagined geography, seen here in close connection to Edward Said’s conception of imaginative geographies as spaces perceived through discourses via imagery and text. Chittaprosad, by retreating to the small territory that was constituted by his immediate neighborhood on the outskirts of Bombay, clearly draws a line and sets up a boundary between himself and the “modern Indian painter’s work.” While there is a certain dose of frustration in the artist’s statement above, it also rests on the reassurance that his addressee, Dr. Krása, as well as the Czech community that he represented for Chittaprosad, approved of him as an artist. In several letters written by the artist to Krása, the artist tells of his pride to have found his “linocuts reproduced in a great journal like NOVY ORIENT [sic].”[40] In the same letters, Chittaprosad also frequently refers to Salaba and Krása as his best friends; he also references Prague and Czechoslovakia, in general, as being places to which his heart is attached and where some of his best friends lived.

By not having accepted any of the several invitations that came to him from Prague, Chittaprosad created for himself an idea about Prague based on associations with certain individuals and institutions, which eventually created for him an imagined geography that came to appear, in the words of Said, “to crowd the unfamiliar space outside [his] own.”[41] His work, within a geography of transnational cultural exchange, came thus to inhabit a position that confirmed him as an artist engaged in peace-building and with an intrinsic mandate to point to social inequalities and geopolitical realities via a realist style and a political stance. The dilemma of being left out of the canon of Indian modernist art discourses connects to the course of his early career, when his works were very much in line with the CPI’s cultural politics regarding iconography and ways of display. Referring to these early works, Sanjukta Sunderason aptly pointed at this predicament by saying that “these images [were] primarily serving purposes of visual reportage and grassroots mobilization [and were thus] not provided with any static institutional space of display, or critical patronage.”[42] This, she assesses, has contributed to “their eventual marginalization within narratives of Indian art practice.”[43]

That this marginalization also provoked the artist to productively and creatively seek other means and avenues to circulate his work is visible in yet another alignment with global ambitions in the postwar period. The cover sheet for the series Without Fairy Tales (fig. 6)—or Angels without Fairy Tales, as it is perhaps better known—is the title page of a series of linocuts that the artist developed in 1952. This collection was dedicated to the International Conference in Defense of Children, and was first published by the Danish UNICEF Committee in 1969.

Fig. 6. Chittaprosad, Without Fairy Tales, 1952, linocut on paper, 29.7 x 30.6 cm. Photo © National Gallery Prague, 2019.

The imagery in this series is dominated by oppressed children whose lives are marked by labor, suffering, disease, and oppression. Little Acrobats (fig. 7), part of this series, renders one such scene where, in a performative act, children vie for attention in order to earn some money. The playfulness of the situation is thus deceptive. In these images, children are not seen in playful circumstances but are, instead, shown to be deprived of childhood.

Fig. 7. Chittaprosad, Little Acrobats, 1952, linocut on paper, 29.4 x 30.5 cm. Photo © National Gallery Prague, 2019.

Chittaprosad’s heightened interest in creating works not only for children but also about children has to be brought into connection with the possibilities that agencies such as UNESCO came to offer in the postwar years. Within UNESCO’s circuitries and programs, artists and artworks were increasingly kept mobile across the world to demonstrate the universal exchangeability of the cause. Chittaprosad’s realist paradigm, in such an environment, became a useful carrier in demonstrating humanity.[44]

The artist’s declared demonstration of humanity is also what constitutes the thirty-eight works that have been acquired by the National Gallery Prague. Many of these works are in fact from the series Without Fairy Tales.[45] It is unclear under what conditions or against which background the National Gallery purchased the works from the artist. The works represent a cross-section of the artist’s oeuvre, with themes such as children and labor, peace, uprising against injustice, the intimate relationship between woman and man, folk art, and idyllic rural scenes. Since the National Gallery purchased the works in 1964/65, it is very possible that this was related to the artist’s first retrospective in Czechoslovakia, which was held at Prague’s Hollar Gallery in May 1963.[46] It can generally be stated that Chittaprosad came to increasingly focus on children, in terms of peace-building and in combination with education. He illustrated a number of books for children, and the target audience for his playhouse Khelaghar were the children from his neighborhood. With little to hardly any recognition during his lifetime in India, children may well be seen to have replaced an absent audience, while at the same time also having become a valuable currency for building a way to mobilize his work within a transnational circuitry.

A summary of the artist’s lifelong concerns, under the pretext of art demonstrating humanity with a clear political stance, can be seen in the film Konfese (Confession). The Czech filmmaker Pavel Hobl made this film in 1972, when he traveled to India after having been commissioned to produce a commercial film for Czechoslovak Airlines.[47] Hobl’s consultant was none other than Miloslav Krása, who suggested that the filmmaker meet the artist Chittaprosad. In an interview with a Czech magazine, the filmmaker tells how difficult it was to approach the very shy artist on the Bombay peripheries, and that the whole shoot only lasted one hour.[48] This is how Hobl came to include not only scenes shot at the artist’s home but also material portraying the artist’s graphic work, along with his work for magazines such as Nový Orient and New Orient Bimonthly. The director’s intention was to portray an artist deeply connected to the cause of peace and humanity via formal elements of social graphic arts and folk art. In an interview, Hobl stated that Chittaprosad’s work very strongly reminded him of Mexican and Chinese woodcuts.[49] The camera thus weaves between images of the artist’s work and home to scenes from the historic Bengal famine (probably from film archives) and the life of rural India. More frequently, the camera zooms in on statues of Indian temples and folkloric festivals, and juxtaposes these images with the puppets and masks at Chittaprosad’s home, as well as details of his works that relate to these figurative elements. Hobl won two prizes for the film, one of which was the important prize at the fifteenth international documentary film festival DOK in Leipzig, where Konfese was awarded the World Peace Council prize. Chittaprosad must have voiced misgivings about the title of the film, for both the filmmaker and Krása appear to bring forth explanations sometime later.[50]

Conclusion

While this instance of misunderstanding points to the dilemma of artistic perception and the problems involved in working across geography and language, it also reveals the productive dialogical exchange that Chittaprosad experienced through a transnational network of cultural circulation that sustained his artistic production over three decades. This article has traced Chittaprosad’s subject formation as an artist and its relationship to a process in which aesthetic choices were informed by a selective appropriation of popular, traditional, and folk elements. The multilayered exchange with institutions and individuals from Prague involved the exchange of the artist’s works. Equally importantly, however, it involved a continued discussion and appreciation of his aesthetics, thereby approving of him as an artist.[51] His post-independence career was largely built along a transnational exchange and support via a group of individuals and institutions from Czechoslovakia, and this is how the artist came to be relegated to a discourse that existed parallel to the dominant discourse on art in India.[52] In a way, the earlier dilemma of Chittaprosad’s being consumed by the CPI as a “people’s artist” is here seen as being repeated, except that now the framework shifted to a solidarity that was constituted by transnational politics, associated aesthetics, and the circulation of cultures.

Acknowledging the artist’s transnational alliance and career and drawing attention to the result of this exchange—from the staging of performances with Khelaghar in Bombay, to his works regularly being featured in Czech journals, to his exhibitions in Czechoslovakia and his works in the collection of the National Gallery Prague—shows that Chittaprosad’s post-independence work was largely shaped in resistance to the “teleological certainty of modernity.”[53] Instead, his reliance on the certainties of the folk and the popular resonated with his Czechoslovak counterparts and their idealistic agenda of celebrating “socialist culture [as] one of the primary agents of the penetration of socialist and humanistic ideas in the world.”[54] The manifestation of solidarity that Chittaprosad conceived of within this transnational network/space was therefore based on socialist ideals and constituted through personal discourses and circuits of visuality. Solidarity therefore provided the artist with a notion of cross-identification with ideological and aesthetic registers.

The predicament of Chittaprosad as a former party artist can thus be understood against the prism of the Cold War, where, along the transnational network between Czechoslovakia and India, solidarity was conceived, imagined, and enacted in aesthetic modes and emotional support via circulatory practices. The fact that Chittaprosad’s career and work unfolded in that cultural space, informed by the “processes of translation and transnational migrations,” points to the necessity of including the defining logic of circulatory practices in a global modernist discourse.[55] It will also have to take into account what sustained Chittaprosad’s post-independence career, namely, the multitude of correspondence along with the very personal contacts that enabled the circulation of his works in a multilayered network of platforms. This can then lead to the assumption that, by “bringing into focus those sites of interaction and shared meaning-making that remain outside of high modernism,”[56] our understanding of modernism can avoid to preclude “creative exchange and reciprocal recognition [and] expand [the] notion of geographies of modernism”[57] to recognize the potential of a transnational socialist solidarity.

Author’s note: The help of Zdenka Klimtová and Jaroslav Strnad in researching archives in Prague was indispensable. I would also like to thank the peer reviewers for their extended comments. These were immensely beneficial to the refinement of this article.