October 11, 2022

Editorial Note

Abstracting Parables is an exhibition triptych that brings together the positionalities of Sedje Hémon (1923-2011), Abdias Nascimento (1914-2011), and Imran Mir (1950-2014) in a partnership between Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and Sonsbeek 20→24. Three readers accompany the exhibition, one on each of the artists. The readers are published by Archive Books and available in our museum shop. Stedelijk Studies is sharing one exclusive essay from each of the three readers weekly.

In this third and last text, writer and curator Nafiz Risvi reviews Imran Mir’s oeuvre. In the exhibition section titled A World that is not Entirely Reflective but Contemplative, Mir’s experimental compositions are a result of the intersections of his design training and influences from modernism.

Visit us soon as Mir’s work will be on display at the Stedelijk until October 16, 2022.

If we can imagine a phantasmagorical play set against the backdrop of the late 70s in which an artist walks the streets of Soho, New York, and modernism’s notions creep through the pavements, into the artist’s shoes, and find their way via musculature and metabolism to the sensibility of the painter, it would explain so much about why Imran Mir painted the way he did for so much of his life.

These were notions of fragmentation of form in search of essential truths, encounters with materiality and an engagement with emotion and feeling. It is undeniable that Mir had already been struck by conceptual art while studying communication design at Ontario College of Design in Toronto (OCAD). His instinctive sense for order, further stimulated by the field of design, nourished his investigative enquiry that predominantly consisted of a geometric mandate in modern art. But, as he told me, witnessing first-hand the paintings and installations in those myriads of small galleries in Soho left a deep and enduring impression on him. And if there was anything Imran Mir ascribed to deeply, it was Barnett Newman’s assertion:

“The meaning must come from the looking, not from the talking.”[1]

And so, he was a man of few words and big ideas.

In 1972, Imran Mir exhibited a playful hedonistic series of paintings that were full of color—a joyous offering at the temple of abstraction. There was no particular compositional principle; the objects were not contained.

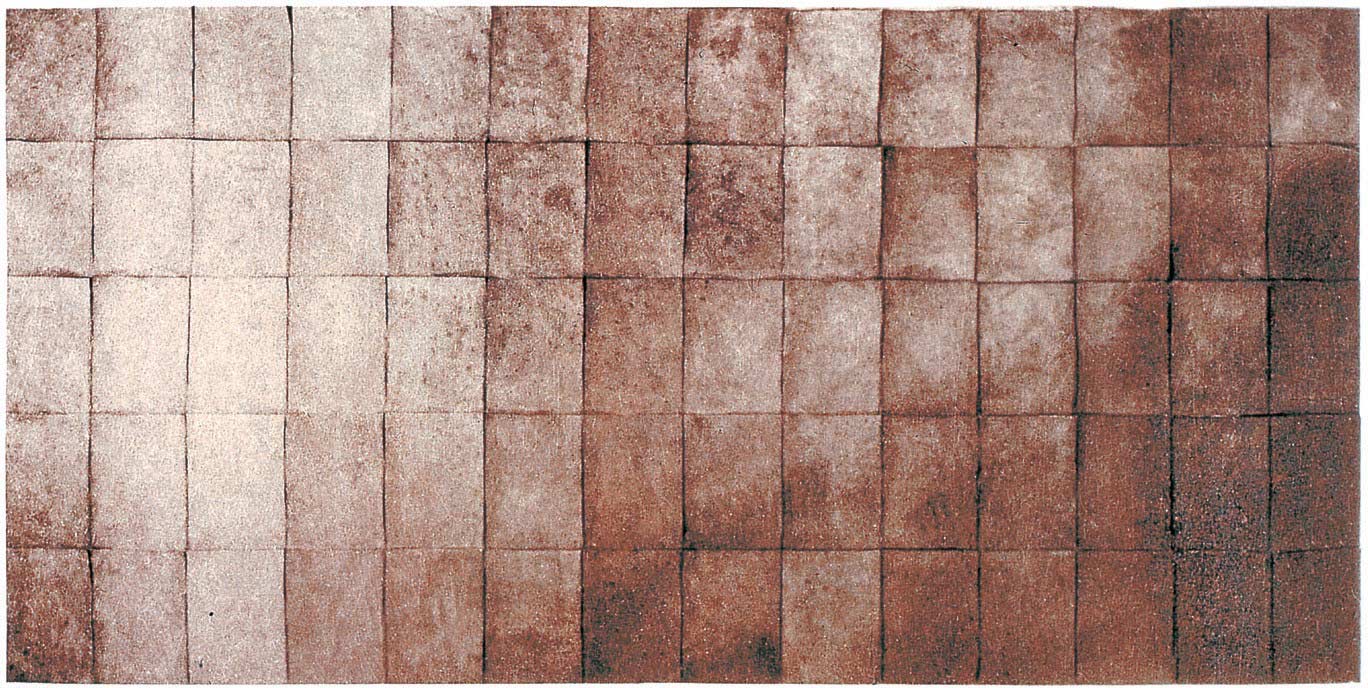

IMRAN MIR

Second Paper on Modern Art, acrylic on handmade paper, 213 x 304 cm Soho Center of Modern Concepts, New York

© Imran Mir Foundation

In 1976, Mir exhibited at Soho Center of Modern Concepts in New York. The installation consisted of 70 acrylic rectangles, set in a grid-like pattern, painted on hand-made paper in earthy russet tonal variations that darkened as the eye moved across the plane from left to right. In 1974, he exhibited another similar installation with acrylic and wax on canvas at Gallery 76 in Toronto, Canada. What was important to the works was Mir’s use of the grid, as it had critical relevance to his perspective as a graphic designer and would forever reflect in his painting—rather overtly in his earlier works, and more subtly in his later practice. But he never abandoned the grid that remained at the core of his training as a designer.

Imran Mir had been influenced by Max Bill, whose workshop he attended in Buffalo, USA. Bill was one of the most famous proponents of the modern movement and a major inspiration in graphic design, but also himself an artist, architect and pedagogue. Bill was trained at the Bauhaus along with Paul Klee, Walter Gropius and Wassily Kandinsky. Bill said: “I am of the opinion that it is possible to develop an art largely on the basis of mathematical thinking.”[2]

The use of the grid was nothing less than a manifesto for the likes of Bill, Josef Müller-Brockmann, and Jan Tschichold: the Bauhaus students who had come to Switzerland. “The grid system implies the will to systematize, to clarify, the will to penetrate to the essentials… the will to cultivate objectivity rather than subjectivity.”[3] As a graphic designer, Max Bill encompassed the principles and views of the modernist movement. His work followed a unified visual order and was composed of purist forms—modular grids, sans serif typography and linear spatial divisions. All these elements are observable in Mir’s paintings throughout his career. However, we notice a modicum of change later, when his emphasis came to rest on the sphere rather than the cube or the triangle and took the logic of its roundness apart in order to manipulate its physicality. What renegade path he may have taken thereon, we may never know.

The early practitioners of modernism in Pakistan were the purveyors of a new genre of art; artists like Shakir Ali (1916–1975, Pakistan) and Zubeida Agha (1922–1997, Pakistan) were steered by the aspiration to do away with stolid conventions—a monolithic classicism and realism. They investigated unexplored forms of expression to suit their visions of an art driven by the modernist encounter. As Simone Wille tells us:

(…) modernism was adapted in search of an expression that would eventually articulate a new sense of place. What artists in this movement undertook was seen as a response to a given physical space—the artist’s location—in combination with a serious approach to the vexing historical and contemporary concepts and narratives associated with it. This process was informed by experimental and formal praxis that helped to establish this newfound sense of place.[4]

Many decades had passed since the advent and passing of modernism and the avid fascination of artists with postmodernism while Mir continued to paint in the modernist style. The fact that his peers went on to explore postmodernist influences never deterred him from his path. He was doggedly infused with the modernist spirit that had flooded him, although the jury is still out on whether he was anachronistic to the times he painted in. Critics in Pakistan waded in a shallow pool of words and understanding, and they explained Mir’s early paintings to be influenced by his design practice. They dismissed it all as alluring formalism, appropriated from Western art, making no effort to locate his art in his progressive persona. In turn, he shied away from exhibiting his work in mainstream galleries, putting it down to lack of space—although it was true that many galleries could not accommodate his large-scale paintings. However, it is important to find Mir’s locus in a postmodern, post-structural world. He disliked the idea of using kitsch in his art and was a purist in many ways, for example, the notion of popular media entering his own installations would not have appealed to him. He reveled in the sensation of painting; materiality was sensual and voluptuous for him. As an exception to the rule, two paintings consist of horizontal stripes with tubes protruding from them: the first has a pail attached to the end of it, and to the second is attached a bicycle pump. These are unusual installations for Imran Mir’s praxis, but if we observe closely, the emphasis lies significantly on the design value of the object. The installation centers the everyday experience of living in the modern world by incorporating ubiquitous objects. The pipe in the pail is reminiscent of zebra crossings on the street. The austere, parallel permutations and set of horizontal bands of color are essential for his motivated impulses. It was a metropolitan and urban view of life, almost like the topography of New York’s skyline as seen from a bird’s eye view.

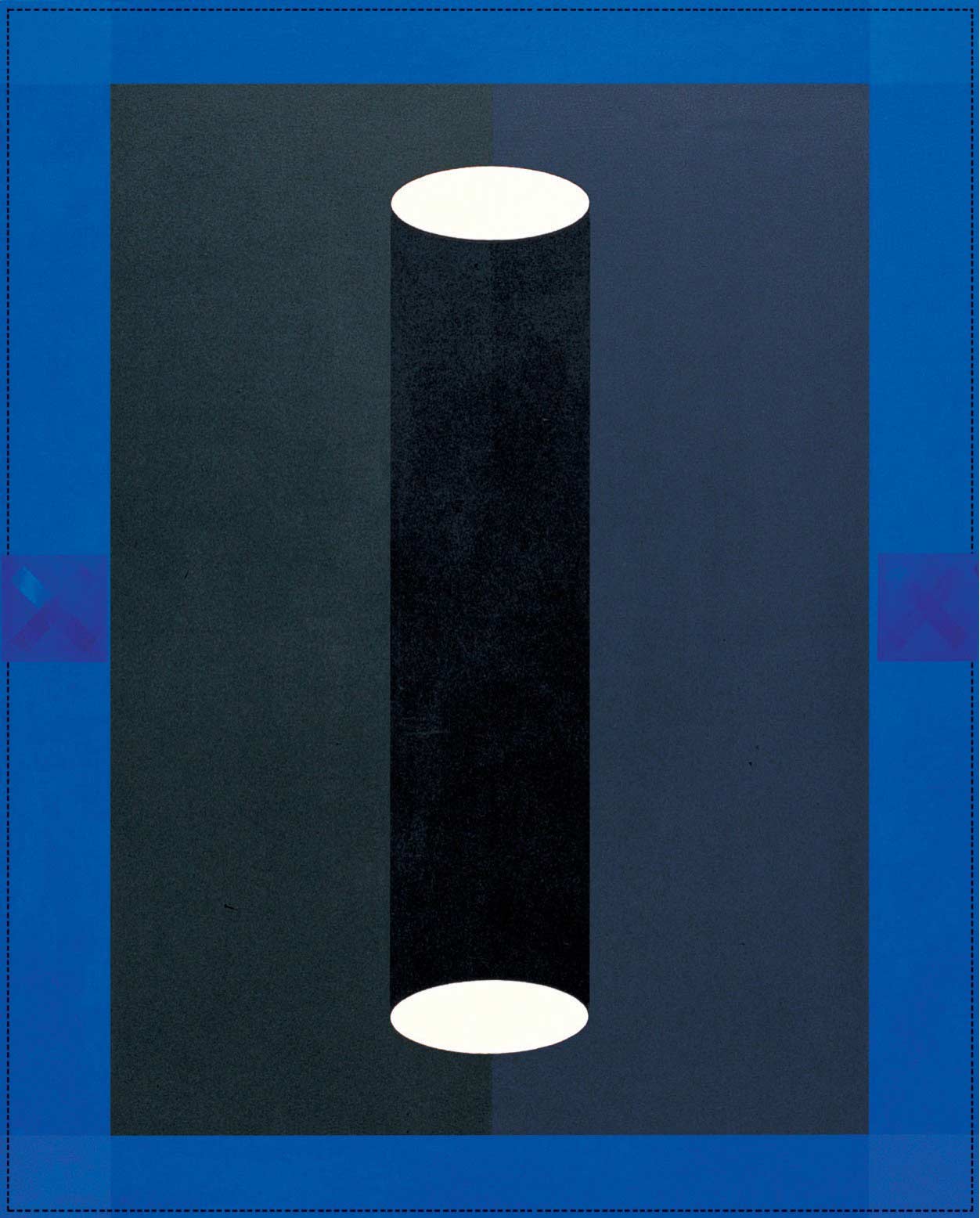

IMRAN MIR

Second Paper on Modern Art, 1978, acrylic on canvas, 213 x 91.5 cm Pipe and pail, dimensions variable, Karachi

(Recreated, first exhibited in Toronto and New York)

© Imran Mir Foundation

IMRAN MIR

Second Paper on Modern Art, 1978, acrylic on canvas, 152 x 91.5 cm Bicycle pump, dimensions variable, Karachi

(Recreated, first exhibited in Toronto and New York)

© Imran Mir Foundation

Yet, immersed as he became in advertising, film and television, he would not allow consumer and popular culture to encroach upon his consecrated field of art. In his final Paper on Modern Art, the twelfth, he used a pair of bellows and constructed a large orb with foam board, inserting on its surface 34,320 plastic eyedroppers. That’s as far as he came to kitsch in his praxis.

When Imran Mir settled down in Karachi in the eighties with his family at the peak of his artistic career, he pursued his day job as a graphic designer, taking the industry by storm with his innovations. But it was art that preoccupied him as a getaway from the diurnal, especially when he became the owner of his own advertising agency and the burden of the business rested heavily upon his shoulders.

Painting was a secret venture, a sensual pleasure. He spoke to no one about his exploratory thematic investigations, about the grappling with memory or celebration, sacrifice or suffering, exuberance or dismay.

Whatever the emotive content of the work, it was made manifest as a personal construct, a set of rubrics that he worked by, both during the day and in the evening in his studio. It was important for him to synthesize the multi-plural experiential vagaries of life and living into a coherent, regulated, self-circumscribed system. Linearity was the journey he was pursuing. The deliberately flattened backdrops were where his existential dichotomies were being played out. The paintings of Imran Mir bore no overt signs of his restless, edgy personality. And that was measured and considered. It was the facture of the line, the plane and the point at which they met in space that created the drama and tension within the painting to build the

narrative. Once Mir had secured the mathematical arrangement of his theoretical representation, he could engage with the formula as he wished. He could revise it, create trompe l’oeil, box it up, erect it and take it apart. It was his to play. The optical illusions he created in his Ninth Paper on Modern Art encapsulate a prolific period of painting.

IMRAN MIR

Ninth Paper on Modern Art. 1996, acrylic on canvas, 183 x 152 cm, Karachi

© Imran Mir Foundation

His mood, as witnessed first-hand by me, was exuberant. His use of pure, flattened, saturated color, as well as the large swathes of pure red, blue or even black, were indicative of his expressive, sweeping gestural freedom from that which had held him back from showing his work earlier. Displaying a self-assuredness and conviction in his own stature as an artist, the colors were reminiscent of what Robert Hughes remarked about Motherwell: “Color in Motherwell is not an adjective but a noun.”[5] This amplitude was contained within the parameters of the rigorous grid that rested at the core of his consciousness and resonated from his training as a graphic designer.

Every painting is a manifestation of order emerging from chaos.

There was reasoning for it all: the color fields; the objects; the cylinders, tubes, cuboids, tetrahedrons, arcs, dots—all existing through a thought logic that played their part in bringing balance and equilibrium to the spatial dimension.

The sets of colors complemented or contrasted each other, creating a visceral perceptual effect. In most of his paintings, the objects lie at the center, pulling the viewer’s attention towards it and then outwards to the smaller semiotics that sit on the outlying peripheries. In the paintings, there are sure to be spaces where the eyes can rest so that the viewer is offered space and time to linger on each element of the painting. The arrangement is, therefore, always thoughtful.

Mir innovated within the considerations of the modernist tradition, and it was in his last and final twelfth paper that we see signs of a profound ontological struggle. Here was a skirmish between the object and the idea. It was something that Mondrian had attempted to do with such piquancy many decades earlier:

Mondrian wipes clean the canvas, eliminates all vestiges of the object, not only the figures but also the color, the matter and the space which constituted the representational universe; what is left is the white canvas. On it he will no longer represent the object: it is the space in which the world reaches harmony according to the basic movements of the horizontal and the vertical. With the elimination of the represented object, the canvas—as material presence—becomes the new object of painting. The painter is required to organize the canvas in addition to giving it a transcendence that will distance it from the obscurity of the material object. The fight against the object continues.[6]

IMRAN MIR

Twelfth Paper on Modern Art, 2014 Acrylic on canvas, 122 x 122 cm, Karachi

© Imran Mir Foundation

It was in the final year of his life that it appeared: Imran Mir was letting go of a recurring object in his paintings, searching for a more transcendental quality. The grid that remained in his work was inoperative and did not function in its role of containment. It was not doing a great job of keeping objects in or out. What looked like the re-emergence of the grid was rather a grid that had lost all of its purposiveness. The grid looks weak, tattered, frayed, and has been punched through. Spheres have dissolved as if some nebulous amoeba had gradually consumed them and the artist had been watching the dispersion of perfection, having found pleasure in the imperfection at last. Mir’s universe had also drifted somehow; it became unpegged from a measurable materiality to a liminal spatiality, yet he owned this space with élan and vigor.

About the Author

Nafisa Rizvi is an independent art writer and curator who shuttles between her current residence in Chicago, USA, and her hometown Karachi, Pakistan. She runs the art blog artmesiartinpakistan.com. Rizvi has curated many shows including Stop Play Pause Repeat, at Lawrie Shabibi Gallery in Dubai in 2012, and They Really Live the Real Reality in Philadelphia’s Twelve Gates Gallery in 2015. Nafisa Rizvi has edited two artists’ monographs: What You See Is What You See, Life and Art of Imran Mir, together with Nighat Mir (The Circuit Limited, 2018), and Rebel Angel, Asim Butt (Markings Publishing, 2014). Nafisa has contributed to numerous books, journals and publications within Pakistan and across Asia and Australia.

[1] As quoted in Michael Findlay, Seeing Slowly Looking at Modern Art (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2017), p. 97.

[2] Eli Maor, To Infinity and Beyond, A Cultural History of The Infinite (New York: Springer Publishing, 1986), p.139.

[3] Josef Müller-Brockmann, Grid Systems in Graphic Design (Salenstein: Verlag Niggli AG, 2007), p.5.

[4] Simone Wille, Modern Art in Pakistan History Tradition Place (Routledge: New Delhi, 2015), p. 2.

[5] Robert Hughes, Nothing if Not Critical (New York: Penguin Books, 1990), p. 293.

[6] Michael Asbury, “Neoconcretism and Minimalism,” in Cosmopolitan Modernisms, ed. Kobena Mercer, Institute of International Visual Arts, (London: MIT Press, 2005), p. 171.