The Political Geographies of Muslim Visibility

Boundaries of Tolerance in the European City

by Luiza Bialasiewicz

First published in Transit 49 (2016, extended German version); Eurozine (2017, English version) and in extended form in the journal City titled “That Which is Not a Mosque: Disturbing Place at the Venice Biennale” (2017).

Introduction

Over the past decade, the question of what has somewhat problematically been termed “the Islamization of space” in European cities has come to the fore of political discussion. Much of the debate has focused on public reactions to and punitive state regulations of Islamic spaces of worship. Examples include the Swiss referendum in 2009 on a ban on minarets, voted in by an almost 60 per cent “yes” majority, and a similar ban proposed in Germany in 2016 by the Alternative für Deutschland. Yet opposition to the construction of mosques across Europe is just the most evident crystallization of wider fears surrounding Muslim presence and visibility in the urban landscape, with a variety of studies noting the emergence of racialized “affective geographies” in response to what are perceived to be “Muslim spaces” and “Muslim bodies,” increasingly demarcating city spaces as safe or unsafe, “ours” or “alien.”[1]

As Nilüfer Göle has argued in Eurozine, Muslim actors, sites and symbols have increasingly become the focus of a “double over-visibilization”:

Public attention to Islam propels Muslims and Islamic symbols to the center of the public space: clichés, images and representations of Islam proliferate in the spotlight. On the other hand, Islamic actors intensify their differences and render themselves more visible as they use the spotlight to gain access to the public space. … This ‘over-visibilization’ takes place in opposition to civic impartiality, which is necessary to public life. Far from being an expression of concerned attention or recognition, ‘over-visibilization’ usually represents a manifestation of social disapproval.[2]

The “over-visibilization” of Muslim presence has reached fever pitch in recent years, so much so that even the virtual presence of Islamic spaces and bodies can provoke often violent “emotional excess.”[3] So much so that even a mosque that is not formally a mosque is able evoke the same sort of response, testing the boundaries of tolerance. The mosque to which I am referring is THE MOSQUE, an art installation that was the Icelandic national contribution to the 2015 Venice Biennale of Contemporary Art. Introduced in its press release as “merely a visual analogue” of a mosque, the installation became something else as the local Islamic community began using it as a temporary site for gathering and prayers, an all-too-real performance that sparked vicious protests and brought the exhibit’s early closure.

THE MOSQUE was the work of Swiss artist Christoph Büchel. Büchel was already well known for his projects that directly intervened into urban spaces and their uses, such as his transformation of a London gallery into an (apparently) fully functioning community center in 2011. For the Venetian installation, Büchel chose the deconsecrated church of the Santa Maria della Misericordia in the Cannareggio district. For the two weeks of the exhibit’s operation, the white baroque facade of the former church gave no indication of what lay inside: there were no panels, no signs linking this space to the events of the artistic kermesse. Only once inside the main entrance did the glass panels of the interior wooden door declare that this was the “Centro Culturale Islamico di Venezia” – “La Moschea della Misericordia” (Venice Islamic Cultural Center – the Misericordia Mosque), with an Arabic inscription above. On a little table alongside the door, green flyers, featuring text in Arabic, Italian and English, announced that: “The Muslim Community of Venice invites you to visit the Moschea della Misericordia,” “the first mosque in the historic City of Venice.” Apart from the web address listed—with an .is extension—and the opening dates, the flyers too gave no indication that THE MOSQUE was, in fact, an exhibit associated with the Biennale. Only turning over the flyer was it possible to notice a very faint stamp in the bottom right corner: “Icelandic contribution to the 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia.”

On the day of my visit, there were a number of curious viewers taking pictures in THE MOSQUE itself, but also browsing the library, reading the various flyers on the walls, and perusing the pamphlets on the tables. It was hard to tell if any or all of these visitors were Biennale patrons – or had simply come to THE MOSQUE attracted by the media publicity the exhibit had generated in Italy and across Europe. At the same time, there were a number of young men who were inside the prayer area; within the installation there was indeed a delineation of a boundary between the religious and non-religious space, with instructions to visitors to remove their shoes and observe Islamic custom should they wish to enter.

It was these instructions and the attempt at the delimitation of a “religious space” within the exhibit that were used as the pretext for the first protests against THE MOSQUE by locals, who lodged a formal complaint with the city authorities within a couple of days of the installation’s opening. Since THE MOSQUE was not a recognized place of worship, they claimed, rules pertaining to places of worship could not be enforced. The ” shoe question” became a particular rallying point, with several protesters forcibly attempting to enter the “prayer space” in shoes, “to see what would happen,” as one particularly feisty woman from the neighbourhood argued, quoted in in the Italian daily La Repubblica.[4]

Nothing, in fact, did happen, since the suggestions regarding the use of the part of the space that was deemed for religious practice were part of the installation. The Icelandic Arts Council responded formally to the “shoe controversy” within a matter of hours of the filing of the complaint, noting that: “Visitors to THE MOSQUE project are NOT required to remove their shoes nor cover their heads with veils.” Inside the exhibition in the Pavilion there is a sign SUGGESTING that visitors remove shoes as a part of the exhibition and the installation, and as a way to respect the cleanliness of the site. “Veils are provided for OPTIONAL use by anyone wishing to use them. It is entirely left up to visitors to choose whether to remove or wear their shoes, and whether to try wearing a veil.”[5]

It is important to note that the calls by protesters to violate the religious prescriptions of a would-be-Islamic space drew upon a much longer history of contestations in Northern Italy of actual spaces of Muslim religious practice. Most famously, in 2005, the right-separatist Lega Nord politician (and for a time vice-president of the Italian Senate) Roberto Calderoli called for “A Pig Day” to desecrate land allocated by the municipalities for the possible construction of new mosques (Calderoli brought a pig of his own to stroll across the plot set aside for a mosque in Lodi).

Delimiting cultural rights

Over 20,000 Muslims live and work in Venice and its surroundings. For fifteen years, they have been campaigning to have a site for prayer within the city, without having to travel over an hour to reach the nearest mosque on the mainland. The project for THE MOSQUE was conceived by Büchel in collaboration with the Islamic Community of Venice and the Association of Muslims in Iceland. The aim was both to answer the local Muslim community’s need for a space for prayer, but also to draw attention to Venice’s own history as a maritime trading republic whose power once extended across the Adriatic and the Mediterranean, and that for centuries was Europe’s “gateway to the Orient.” It was in Venice that the first printed edition of the Qu’ran was made in the sixteenth century, and it was Venice that, for many centuries, was the key point of exchange for ideas and goods between Europe and the Near and Far East.[6]

The city today continues to testify to that past, whether in the Byzantine influenced architecture of its key landmarks, including the Basilica di San Marco, or in countless other material traces and presences, such as the turbaned figures that still stand watch on the Campo dei Mori, the “Square of the Moors.” Before it was widened in the sixteenth century, the Piazza San Marco itself was modelled on the courtyard of the Great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus.[7] It is important to remember these shared histories—to remember that Venice and Damascus were once part of the same Mediterranean cultural space, and inspired one another—in order to challenge contemporary attempts at the delimitation of “cultural” rights to the city on the basis of mythologized versions of the urban past.

Indeed, Venice’s “Oriental” legacy was not the one that the opponents of THE MOSQUE wanted to see being made publicly visible in Venice’s historical center. Led by local politicians from the far-right party Fratelli d’Italia and the right-separatist Lega Nord (which currently governs the Veneto region), pickets began outside the installation the very day of its opening. “This is an unauthorized place of worship—not a work of art. It must be closed immediately,” thundered Sebastiano Costalonga of the Fratelli d’Italia; the Venice municipality should, he demanded, grant the party permission to distribute “informational material” in the square outside of the installation “to let citizens know what is really happening.”[8]

While local politicians calling for THE MOSQUE’s closure focused largely on the legal question of the functioning of an unauthorized place of worship, self-designated “spontaneous citizens” committees’ staged protests in the streets surrounding the installation. One set of flyers, plastered on the surrounding buildings and handed out by protesters, appealed to the Madonna of Nicopeja, the icon that since the thirteenth century has hung in the Basilica di San Marco, having arrived in Venice from Constantinople, looted as part of the spoils of the Fourth Crusade. Venetians have been particularly devoted to this Madonna, which is said to have protected the city from war and pestilence through the centuries. “Santa Vergine Nicopeja,” read the flyer, “we as your children, afflicted by the sacrilegious profanation of your Monastery of the Misericordia in Venice, pray to you, like in the past in the struggle against pestilence and wars of self-defence: take up […] the humble prayer of your people […] protect your Church in adverse circumstances. Come to our assistance in this hour of need.”

Such appeals to divine protection against the profanation of putatively Christian spaces are not new in the Veneto region nor, alas, in Italian national politics. They are instantly recognizable to the Italian public and draw on a long-standing set of symbolic geographies, promoted by the Lega Nord but also other right of center politicians. These focus on the threat of creeping Muslim invasion of Italy and Europe, decried as “Eurabia.” Many of these appeals use language and images lifted directly from the Crusades; over a decade ago, pundits such as, most famously, Oriana Fallaci, were already warning of an Islamic “reverse crusade” that threatened to “submerge and subjugate Europe” through the creeping colonization of European cities.[9] With appeals to just such crusading imaginations becoming increasingly dominant on Europe’s nativist far-right (both in the West and the East), it is important to recall their much longer genealogies.

The geographies of visibility

When the Venetian authorities closed down the exhibit just two weeks after its opening, they made no reference to the violation of religious or cultural sensibilities, or even to the lack of a proper permit for a place of worship. Rather, they cited potential “health and safety” dangers. The recourse to rules of “proper” public conduct and public health and safety to regiment both the building and use of Islamic places of worship has been a recurrent strategy in cities in the UK, the Netherlands and Germany. In Italy, the construction of mosques has met with strong resistance for over a decade. The Lombardy region (like the Veneto, also currently governed by the Lega Nord) recently attempted to impose a region-wide ban on mosque construction; the proposed regional law was, however, struck down in February 2016 by the constitutional court. Since even the Lega Nord could not get away with directly banning places of Islamic worship, the legislation centered on the question of appearance: it forbade the construction of buildings with “bell-towers that were too high” and that “would conflict architecturally with the urban landscape.”[10]

In Tessera, on the Venetian mainland, right across from the airport (appropriately named after the famed explorer of the Orient, Marco Polo), a new mosque is being built. Debates have also centered on its size, appearance and visibility. As long as it is inconspicuous, blending into the warehouses and car dealerships that surround it in this strip of peri-urbanized countryside, “no one will complain,” as one local journalist put it. Similar logics can be observed elsewhere in Europe: in the UK and Germany, for example, “invisible” Islamic religious spaces (or “store-front mosques”) occupying mundane buildings have not aroused the same sort of reactions as purpose-built mosques.

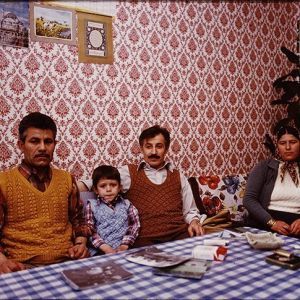

Fig. 2. Nicolò Degiorgis, Hidden Islam (2014), published by Rorhof. Courtesy of Nicolò Degiorgis and Rorhof.

Yet the invisibility of these places of worship raises important questions for rights of presence and participation in the city. While keeping places of Muslim worship inconspicuous to non-attendees may serve to preclude the sort of reactions that “mosques-that-look-like-mosques” frequently unleash, keeping such spaces “hidden” also serves to hide their attendant communities, effectively sorting and segregating them not just out of sight, but also out of the public sphere.[11]

However, the relationship between visibility, physical presence, and political inclusion is by no means straightforward: visibility and presence do not necessarily equal recognition or inclusion. Various strategies to “claim space” in urban centers by marginalized or excluded groups usually fail to ease access to the public sphere or to “the public.” They may serve to create momentary episodes of ” publicity,” but often remain only that: contingent moments of visibility.[12]

Demarcating the right to visibility

Commenting in the Venetian newspaper La Nuova in the days following the closure of THE MOSQUE, Ida Zilio Grandi, Professor of Arabic Studies at Venice’s Ca’ Foscari University, drew attention to precisely this lack of visibility. Coupled with a lack of knowledge, it was, she argued, largely to blame for the reactions of the public to the Biennale initiative:

There is very limited knowledge of the Other [here], and no attempt to learn more. And then there is the tendency to confuse ‘real Muslims,’ those who live alongside us and whom we encounter daily, shopping at the supermarkets as us, with some entirely abstract idea of ‘Islam’ which is seen as a threat. […] Whether you like it or not, Muslims are also ‘us’. People forget that there are already Islamic places of worship here, just not visible ones. So the real problem is their emergence.[13]

The question of “emergence” is a crucial one. When local Islamic associations were first approached by Büchel and the Icelandic Art Center with plans for the initiative, the response was very positive. A New York Times interview with Mohamed Amin Al Ahdab, President of the Islamic Community of Venice, just days before the opening of the initiative summed it up: “Sometimes you need to show yourself, to show that you are peaceful and that you want people to see your culture.”[14]

But how, where, and by whom such “making visible” occurs is not inconsequential. In her writings on the condition of the refugee, Hannah Arendt argued that visibility in the public realm is constituent of full belonging to the political community; that a publicly recognized “space of appearance” is the very foundation of entrance into the political world. At the same time, however, Arendt argued for the necessity of a complementary private sphere of “invisibility”—a space of “mere giveness” that allows the political subject, the citizen, to be just what she or he “is.” Those reduced to the condition of the “refugee,” she suggested, were made both wrongfully invisible and wrongfully visible; they were denied access to the public “space of appearances” while simultaneously thrust into the public in “their natural giveness.”[15]

A growing body of scholarship on the “illegalization” of migrants in European cities has begun to draw on Arendt’s reflections, to highlight what Marieke Borren has referred to as “pathologies of in/visibility”.[16] These studies have noted the concurrent denial of public visibility to migrants, entailing a forcible drawing of boundaries of who is allowed to appear in public space (physically, but also in the Arendtian political sense)—and at the same time the forcible “making visible” of migrant bodies as a security and public threat. The “veil question” has long been indicative in this regard: while the right to wear a veil (whether full or partial) has been the object of legislation explicitly focused on the delimitation of the right to display religious symbols in public space, it has frequently been appeals to public order and security that have served to justify the various bans currently in place across Europe (whether at the national, regional or local levels).

The forcible “over-visibilization” of Islamic bodies, to use Göle’s term, sadly became part of the political hysteria sparked by the “refugee crisis” of 2015. The “crisis,” initially presented as a crisis of the EU’s borders, quickly shifted in political discourse from being simply a question of “external” border management to a question of maintaining “internal” order, especially in the European cities that were the initial destination for many of the refugees. The fixation on “maintaining order” pertained not only to member states’ physical and institutional reception capacity, however. Faced with hundreds of thousands of mostly young male refugees, the popular and political rhetoric decrying large-scale immigration quickly broadened to include risks to the EU’s very stability and public safety.

The events in Cologne on New Year’s Eve 2016 were a turning point in these discussions: the refugee-as-potential-terrorist also became re-scripted as the refugee as potential rapist, molester and abductor of European women. Politicians in Austria, Poland, Germany and the Netherlands called with one voice for the protection of women’s bodies from the threat posed by the mostly Muslim “refugees” and “asylum-seekers” now roaming the streets of European cities, uncivilized men who posed a direct threat not just to public order, but also to “European values” and “civilization.” Such rhetoric clearly delineated who was to be feared, and whose presence was to be policed in the city; the threat of sexual violence was limited to one specific population, and reliant on a series of physical and geographical distinctions.

Needless to say, such narratives hold many parallels with colonial histories. This goes not just for subsequent calls to “(re)educate to integrate” evidently uncivilized new arrivals, but also for wider appeals to “the woman question.” Historically, the trope of “white men saving brown women from brown men” has been employed to justify interventions to “liberate” women across a variety of colonial contexts, from British rule in South Asia to French colonialism in North Africa, a “colonial feminism” that Leila Ahmed and others have denounced.[17] In 2016, the “brown men” that suddenly appeared on the streets of European cities were thus immediately “naturalized” in their predatory, uncivilized form, and made forcibly visible in their potential for violence—both terrorist and sexual.

Sadly, this kind of explicitly racist stereotyping and scapegoating is not only a leftover of colonial imaginings, but part of more recent nativist politics in Europe. The putative “Muslim civilizational threat” has become increasingly sexualized over the last decade in populist right-wing rhetoric, while appeals to the protection of “sexual rights” have been used by various parties across the EU to rationalize restrictive immigration policies and other practices that limit the public presence of ethnic and religious others.[18] As Eric Fassin puts it, “sexual democracy [has become] the language of national identity throughout Europe—in the context of an anti-immigration backlash, gender equality and sexual liberation are a litmus test for the selection and integration of immigrants, in particular from the Muslim World.”[19]

Both the policing of Muslim bodies in urban areas and the delimiting of spaces of prayer (actual, or artistic) draw our attention to wider struggles over the political geographies of visibility. These struggles are not only about who has the right to appear in the public spaces of European cities but also—and above all—about who has the right to be part of “Europe” itself.