Preamble

My father never spoke to me about his family’s migration, part of an unprecedented shifting of populations that took place in eastern parts of central Europe toward the end of the Second World War. He was thirteen then; fleeing the Red Army with his mother and younger siblings from a town in Lower Silesia (today’s Trzebnica in Poland) to Bludenz where his uncle lived. Or perhaps I simply failed to listen, to show interest in his past. The traumatic experience, I have been told by members of the family, shaped his life.[4] He was to engage himself professionally (as a jurist) for asylum seekers, refugees, and migrants, and personally from the late 1980s onward (as editor to the local Silesian journal). Writing this essay gave me the opportunity to address both his forced expulsion and later travail, and to reposition myself toward him.

The Catalan psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and physician Francesc (also known as François) Tosquelles (1912–1994) may contribute to these reflections. From 1939 onward, Tosquelles spent his exile in France. Founder of the movement for institutional psychotherapy, he developed his experimental practice at the Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole Psychiatric Hospital in the department of Lozère, forging links to discoveries of psychoanalysis, phenomenology, and anthropology. If his work has been termed radical and innovative in its linking to politics and culture, it is without doubt his personal experience alongside professional encounters that contributed to developing his groundbreaking clinical concepts and methods.[5]

Foregrounding the trauma of exile and migration, around 1943 Tosquelles introduced his idea that would later become known as la méthode hypocritique (the hypocritical method). “When we amble around the world,” Tosquelles noted, “what counts isn’t our head but our feet. Knowing where to tread.”[6] According to Tosquelles, the exile one is experiencing is more often than not registered in the soles of one’s feet, as feet cross borders. This transfer of cognitive experience from the head to the feet struck me as crucial, as it signals a decisive shift in locus—a shift, so important for our faculty to differentiate. This shift in locus also made me think of a sentence by filmmaker and writer Alexander Kluge. As Kluge interrogates in Chronik der Gefühle (Chronicle of Feelings, 2000): “Head of passion (opera); what would be its foot/base/root?”[7]

Diasporic belonging through cultural production

This paper offers some reflections on, and interrogations of “diasporic belonging through cultural production.”[8] Exemplary in this respect, I argue, is An Opera of the World (2017) by cultural theorist, filmmaker, writer, and scholar Manthia Diawara. Diawara’s filmic essay, first shown at documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel in 2017, provides, I suggest, a point of vantage from which to reflect on the thematic focus that Stedelijk Studies sets out to explore in this issue: the diaspora.[9]

As a diasporic subject, Diawara grounds his work, as Julia Watson writes, “in an autobiographical discourse, filtering his arguments through a ‘politics of the personal.’”[10] Born in Bamako, Mali, in 1953, Diawara spent his childhood in Guinea until 1964, when Ahmed Sékou Touré’s regime expelled his family from the country. With an education obtained in Guinea-Conakry, Bamako, and Paris, he migrated to the United States to pursue his doctoral studies. If Diawara situates his critical thought “within his own cultural and visual experience,” as Watson notes, it is also within that of “the larger ethnos […] of diasporic Africans […].”[11] This is reflected in the many essays and books Diawara authored about film and literature of the African Diaspora. Diawara’s major autobiographic works In Search of Africa (1998) and We Won’t Budge: An Africa Exile in the World (first published in 2003) trace his experience living as an immigrant in France and the United States. The shifts in perspective at stake in these works, from the personal to the collective, also characterize his films. As a filmmaker, Diawara collaborated with Kenyan writer Ngûgî wa Thiong’o on a documentary about the renowned Senegalese writer and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, Sembène: The Making of African Cinema (1994), to later direct, among others, Diaspora Conversations: from Gorée to Dogon (2000) and Edouard Glissant: One World in Relation (2010).

Diawara’s most recent films and installations include AI: African Intelligence (2022), A Letter from Yene (2022),[12] and Toward a New Baroque of Voices (2021).[13] This latter montage of voices, in the form of dialogues on Africa and the African Diaspora, includes previously recorded interviews with Martinican poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant, followed by others such as American artist David Hammons, French filmmaker and anthropologist Jean Rouch, or Nigerian dramatist and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka. Diawara, who speaks several West African languages, including Malinké, Sarakolé, and Bambara, in addition to French and English, divides his time between homes in Yene (Dakar), Senegal, and New York, where he is a distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature and Cinema Studies at New York University, as well as Director Emeritus of the Institute of African American Affairs. Diawara continues to be a key figure in West African diasporic cultural production.[14]

Manthia Diawara, An Opera of the World, 2017, Manthia Diawara on the island of Lesbos. © Manthia Diawara. Courtesy of the artist and Maumaus/Lumiar Cité.

Challenging fixed ideas of identity, place, history, and belonging, Diawara’s An Opera of the World is imbued with the poetics of relation. A poetics manifestly indebted to Glissant, with whom Diawara shared a deep friendship. How to share one’s intuition with another person’s intuition? Manthia Diawara asks elsewhere. If I insist on this tentative, intuitive venturing, it is because it is indicative of the resounding background against which Diawara makes his geste toward opera and film, toward Glissant. Yet beyond this clear debt to Glissant, it is important to note the scope of Diawara’s undertaking. Many voices have informed An Opera of the World. It is this relational polyphony at stake in Diawara’s essayistic film that I want to examine.

About two years ago, I was in conversation via Skype with the producer of An Opera of the World, the curator and artist Jürgen Bock, who established, among many other things, the prestigious Maumaus Program in Lisbon. Bock and I met in Antwerp in 2015, in his role as curatorial advisor for a pioneering doctoral position in Curatorial Research, developed at the M HKA (Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp) in collaboration with the Lieven Gevaert Centre as part of a larger research project.[15] A position I was fortunate to hold within the museum’s Collection Department. During our conversation, Diawara’s name resounded several times. This was not surprising, as I knew of their close working relationship. The latter gave rise to an earlier Maumaus production of Diawara’s Maison Tropicale (2008), followed some years later by an exhibition held at Bock’s exhibition space, Lumiar Cité, in which Wole Soyinka and Léopold Senghor – A Dialogue on Negritude (2015) was shown. When Bock told me about An Opera of the World, I still had not seen it, despite its double bill premiere at documenta 14 and subsequent screenings. And so, he kindly offered to send me the film’s preview link for the long winter evenings I was facing then due to a pandemic lockdown.[16] To be honest, it was only several months ago in Madrid while doing research on the work of German polymath Alexander Kluge and his recent operatic productions that I remembered Bock’s message. To make the connection, I went back to the link to view Diawara’s film.

An Opera of the World is Diawara’s cinematic retelling of Bintou Wéré, a Sahel Opera (2007), as performed in Bamako in 2007. As its primary focus, Diawara’s film addresses the relationship of migration and displacement between Africa and Europe, past and present. Shot in Bamako, Munich, and Strasbourg, as well as on the island of Lesbos, the film medium caters to Diawara’s concern; that of interlacing locations, temporalities, and modes of discourse, forging links across oceans. Diawara’s film brings together popular African storytelling, traditional Sahelian music, and European opera. “What happens,” documenta 14 curator Monika Szewczyk asks, “when opera moves south, from Europe to Africa, just as so many people from that continent are moving north, in search of better lives?”[17] In an essayistic approach, for Diawara, An Opera of the World “was also about testing the power of the opera genre to break boundaries, to go from culture to culture, continent to continent; if not by changing the form of traditional opera, then at least by changing its elements.”[18] The film medium thus offered Diawara the means to play with the elements of the original opera freely, “by changing some and omitting others,” by interchanging African and European arias, African migrants and Asian and European migrants.[19]

At the same time, Diawara makes use of archival material, footage of migrants and refugees, mostly taken from newsreel. He presents this material in loose, short segments, telegraphic in style, together with “discursive commentary drawn from interviews, performances, and [his] own autobiographical musings in voiceovers,” as the film reaches backward and forward.[20] In returning nearly ten years later to the rushes he had filmed in Bamako of the opera rehearsals, Diawara found himself faced with interrogations that were to form the basis of his operatic film—to question the porosity of frontiers, of cultures, of music. Probing the power of the opera genre to overcome boundaries, to transform itself in relating to diverse cultural practices, modes of thinking and being, this paper addresses the core concepts in Diawara’s staging and speculates on some possible approaches to a “chorus of relations.”

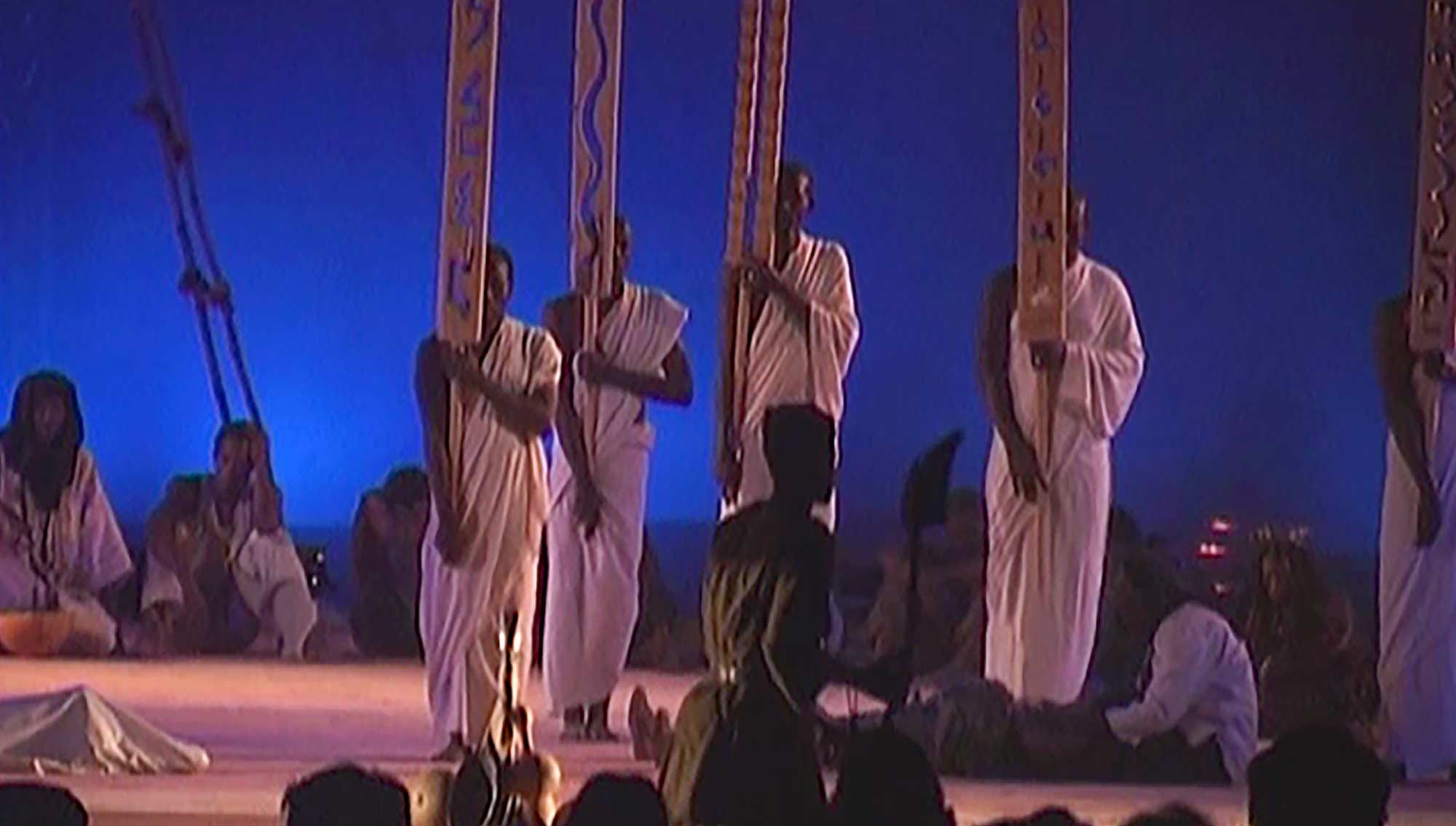

Bintou Wéré, a Sahel Opera

An Opera of the World brought Diawara back to his hometown of Bamako to film performance rehearsals of the 2007 production Bintou Wéré, a Sahel Opera, originally commissioned by Prince Claus of the Netherlands.[21] It was a contemporary African opera billed as the first of its kind and performed on an outdoor stage on the banks of the Niger River by a cast all trained in Africa.[22] Composed by Guinea-Bissau’s Zé Manel Fortes and based on a libretto signed by the Chadian poet and playwright Koulsy Lamko in collaboration with Senegalese artistic director Wasis Diop, the opera relies on Griots and traditional African songs.[23] After its avant-première in Bamako, first performances were held in Amsterdam and, following rehearsals at La Manufacture des œillets, at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris.

What Diawara was filming in Bamako was a contemporary story about the torments of migration, told in operatic form. A caravan of young Africans in their journey across the Sahara Desert to attain Europe in the hope for a better future. The journey’s protagonist and spokesperson for the group, Bintou Wéré (Djénéba Koné), a former child soldier and young woman from Mali, finds herself pregnant after being raped in her village by senior community members. Wéré rebels against the local patriarchy and sets out to Europe with the group.

Diawara, in his remake, a sort of tribute to Lamko’s libretto, freely interprets the themes of the opera, in which movement and immobility eventually become matters of life and death. If Diawara places his focus on the opera’s key characters, it is with the intention that the performances mirror the larger drama at stake: the world’s current, ongoing migrant/refugee crises. Among the characters Diawara singles out are:

The traditional Griot, who advises the youth not to leave home; the more modern Griot, who flatters the youths that have returned home with wealth and prestige; the leader of the disenfranchised and dehumanized youth, who is determined to leave home and defy deserts and oceans to reach Europe; the corrupt smuggler; and Bintou Wéré, the pregnant young woman who wants to give birth to her baby in Europe, a guarantee for acquiring citizenship.[24]

Manthia Diawara, An Opera of the World, 2017, a scene from ‘Bintou Wéré, a Sahel Opera’, Bamako. © Manthia Diawara. Courtesy of the artist and Maumaus/Lumiar Cité.

The opera follows the caravan from a small Sahel village to the barbed-wire border of Melilla, where Bintou Wéré expects to give birth to her child. The journey across the desert is exhausting and strewn with pitfalls. She challenges the greedy smuggler Diallo (Carlou D), who does not deliver on his promises. Sitting on top of a ladder at the barbed-wire border, Wéré gives birth to her child. She engages in a last dialogue with the chorus, debating whether her child should be raised in Europe or Africa. Yet, ultimately, she does not find hope for her child.[25]

Opening his film to the timeless drama of migration, Diawara interlaces documentary and archival images with scenes filmed during the opera’s performance rehearsal. In so doing, Diawara makes the genre porous. An Opera of the World thus brings together the destinies of Syrians fleeing the war with those who fled during the Second World War, with those of African refugees. At the same time, Diawara is at pains to articulate: “I did not want to respond with the nationalist sentimentalism which consists in advocating for everyone to stay at home, to return to Africa, etc.,” he concedes. “No, I thought of the Greek tragedy, and of Medea, who kills her children rather than seeing them live under certain conditions.”[26] The film’s prologue aptly points to this network of interrelationships.

What is more, it is through montage that Diawara’s ambitions become clearest. Montage in this sense, I argue, is not only where the essayistic in Diawara’s work can be located, but also where different experiences act upon one another, where a relational, diasporic poetics comes to the fore. Spurred by the invitation in 2016 to participate in documenta 14, in Diawara’s account, Athens became the site of encounter with a Syrian diasporic subject, the film editor Kenan Akkawi, to whom Diawara entrusted the film’s montage during the two months of their collaboration (at a moment when the European refugee crisis was at its peak).[27] Hailing from a family of filmmakers, Akkawi, who left Syria for Greece more than thirty years ago when he was a boy, grew up in Athens (he speaks Arabic, Greek, and English fluently, in addition to some French). Far from being spelled out in the film, Akkawi’s diasporic experience is actualized (“rendered immediate”); it drives the montage—in-between the image plane and the plane of sounds/music. Diawara activates these processes—between what is visible and what is not—from an ethical logic. It is here where Diawara’s commitment lies.

Manthia Diawara, An Opera of the World, 2017, a scene from ‘Bintou Wéré, a Sahel Opera’, Bamako. © Manthia Diawara. Courtesy of the artist and Maumaus/Lumiar Cité.

Prompters

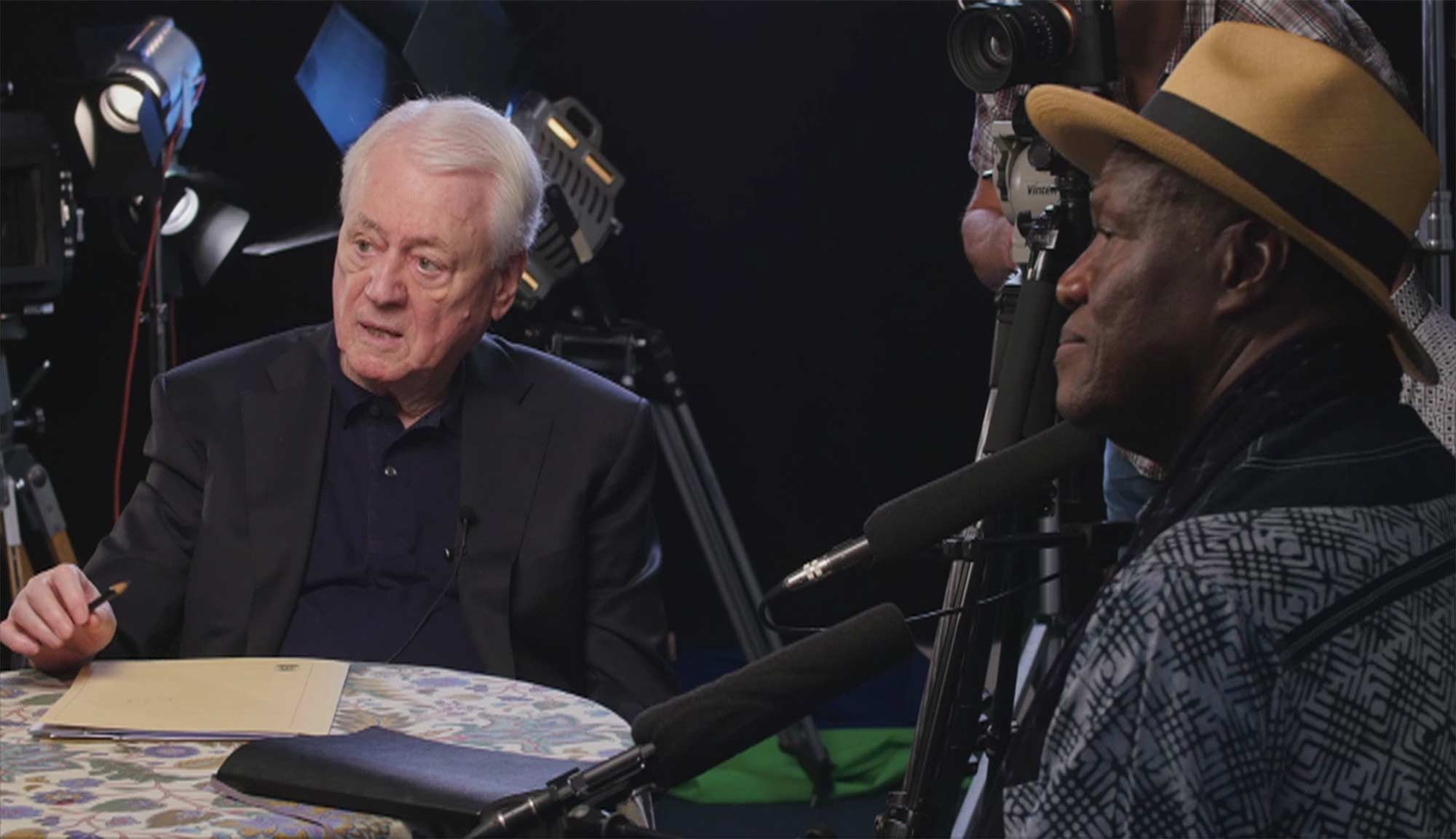

Sitting next to Manthia Diawara in his studio in Munich in 2016 and viewing An Opera of the World together—in a mise-en-abyme of sorts—on a computer screen, Alexander Kluge foregrounds the impressive scenes of mourning that feature in Bintou Wéré, a Sahel Opera. Scenes which reoccur at different moments in the film. “And when you put ‘Lamento d’Arianna,’ […] composed by Monteverdi, beside it,” Kluge notes, “[they] would be friends. They are different, it sounds different, the instruments are different,” yet “the feeling is universal.”[28] Kluge’s comment is crucial in that it helps to underline the differences and points of contact at stake in An Opera of the World. The German author and filmmaker is present from the film’s beginning with a prologue he signs on opera. Kluge also stars in the film as one of the “prompters” Diawara takes recourse to. As part of the roundtable discussions generated in the film, “Kluge’s definition of opera is different from but not necessarily opposed to” the understanding of, for instance, librettist Koulsy Lamko. “This,” Akin Adesokan suggests, “is Glissant’s tout-monde in practice.”[29]

Elsewhere, Diawara accounts for Kluge’s key role in working toward An Opera of the World in that Kluge helped him “to tell the African story that would actually tell the human histories of Europe from the Greek to today.”[30] To be sure, Kluge’s recent filmic, literary, and curatorial projects are to be seen in line with his longstanding interest and consistent engagement with the phenomenon of opera. Perhaps with Kluge’s own operatic deconstructions in mind, achieved through literary and cinematic means, Diawara inquires: “I ask my prompters, can the opera genre be deconstructed, so that we may bring opera back to the plebeian statue, to the masses?” “And could […] migration,” he goes on, “be one of the popular stories to sing about, cry with the tragedies, laugh or mourn with the characters?” For, as Diawara makes clear, again in reference to Kluge’s own ruminations on the subject,[31]

The experience of collapsing opera and film—the classical and the profane—was not only a way to enrich my filmic vocabulary, but also a gesture towards the liberation of the genre of opera from its classical and “sacred” environments in the West.[32] Thus, the project gave me an opportunity to deliver operatic emotions on screen, by combining African and European songs, without placing hierarchies between them; by interlacing sacred and popular songs and placing them over images from Africa, Asia and Europe […].[33]

Manthia Diawara, An Opera of the World, 2017, Manthia Diawara in discussion with filmmaker and writer Alexander Kluge, Munich, 2016. © Manthia Diawara. Courtesy of the artist and Maumaus/Lumiar Cité.

Further views are obtained by other experts Diawara invites as prompters. “Together,” Diawara notes, “they help me to structure and move my story forward, and to show that throughout human history such movements (migrations and emigrations) have often resulted in the creation of new and dynamic humanities, rather than negative and fearful cultural asymmetries.”[34] Apart from Glissant and Kluge, Diawara’s prompters include the American sociologist Richard Sennett,[35] activist and journalist Agnès Matrahji, French cultural critic Nicole Lapierre, and Senegalese-French novelist Fatou Diome. “From these varied perspectives, Opera weaves a polyphony of voices that resonates as a kind of spoken opera.”[36]

Chaos-Opera

Édouard Glissant, it has been reported, wished for the presence of at least two languages in any event. Ideally even more.[37] The poetry evenings with poets from around the world that Glissant organized in Paris at the Maison de l’Amérique Latine brought this wish to fruition. Poems were read aloud in their language of creation.[38] This is what Glissant came to call the celebration of multilingualism. And Glissant was very keen on there being no translation (at least not immediately). The emphasis was placed on the act of listening. Glissant’s notion of “Chaos-Opera,” as Sylvie Glissant explains, is related to this kind of multilingualism. As Glissant would say, “J’écris en présence de toutes les langues du monde” (I write in the presence of all the languages of the world). Glissant’s statement finds resonance in the words of Kluge. Multilingualism, for Kluge, namely the different languages of the soul within us, like music, necessarily accompanies our speaking. In his film, Diawara foregrounds the multilingualism at stake in the opera performance. Echoing Glissant, he intones the importance of every voice, every language. It is in this sense that we may understand Diawara’s choice of title in relation to the notion of “Chaos-Opera,” which Glissant employed to designate relations in the All-World—an investment in difference as a site of exchange and relating. As such, Diawara’s position in the world as a Malian and diasporic subject, I argue, extends to a positioning and vision/sense of the world itself.[39] In it lies the profound Glissantian poetics of Diawara’s work, powerful enough to change the ways in which we perceive and apprehend the world.

Worlds

How might this case study inform the critical discourse of the diaspora as a way to reflect on the diversity and multiplicity of voices within the collection of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam? What context can the museum offer, and what are the conditions for its artworks to enter into dialogue? If the museum allows itself to be affected by the artworks it collects, to what degree can it be affected to reimagine itself, seeking a plurality of transformation?

I want to come to these questions by way of Édouard Glissant.[40] Concerned with finding that “what keeps us together” through difference, Glissant had his very own idea of a museum. He imagined it as an archipelago, and planned to build it on the Caribbean island of Martinique—plans that eventually did not materialize.[41] The way he conceived it, the museum would “[…] have housed not a synthesis, serving to standardize, but a network of interrelationships between various traditions and perspectives.” According to Glissant, the museum “would not illustrate previously established findings, but function as an active laboratory.”[42] A coming together of different arts. Vital to his conception of the museum was the creation of a meeting point between artists and writers/poetic voices, cooperating, working together, finding common ground in our shared multiplicity, all the while resisting the leveling out of differences. Glissant’s thought is informed by the very geography of the Antillean archipelagos, a group of different islands without a center, yet each endowed with a distinct culture.[43]

How precisely, then, might Glissant’s idea inform the critical discourse on the diaspora at stake in this issue? In my view, Glissant’s conception of a museum not only as place of dialogic exchange but also as a place of difference and potentiality is key here. This potentiality is expressed by Glissant in the following way: “Because, in the end, the idea [of a museum] today is to bring the world into contact with the world, to bring some of the world’s places into contact with other of the world’s places […].” And, he concludes, “We must multiply the number of worlds inside museums.”[44]

Chorus of Relations[45]

Similarly, Diawara’s opera casts its nets wide to compose a complex musical montage, seeking to multiply and expand the notion of opera for the twenty-first century. In An Opera of the World, Diawara takes “opera” as a place from which to create such vital spaces of relations, not least of diasporic belonging. A multilayered montage, Diawara’s filmic essay gives voice to stories and experiences from the history of human migration that encompass Diawara’s own personal history as a diasporic subject. It is precisely this stress on orality that makes his film of particular interest. The porosity and displacement that opera obtains in Diawara’s hands allows for interstices through which multiple voices and images pass, bringing together present, past, and future. At the same time, Diawara’s work seeks to probe the permeability of (pre)established boundaries and forms of expression. In this search for new spaces that Diawara has embarked upon, he upholds Glissant’s “trembling” thought to explore the relations between “different people and places.”[46] Glissant’s concept of the archipelago relays to his la pensée du tremblement. That is, a thought that characterizes itself—poetically, socially, and politically—as being far from all certainty, enclosure, and reduction. Tremblement was for Glissant the way through which we should listen to the world, to perceive it:

“Trembling” thought […] is first of all the instinctive feeling that we must reject all categories of fixed thought and all categories of imperial thought […]. The All-World trembles; the All-World trembles physically, geologically, mentally, spiritually, because the All-World is looking for the […] point where all the world’s cultures, all the world’s imaginations can meet and hear one another without dispersing or losing themselves.[47]

At the same time, Diawara’s Opera of the World brings together differences as a way of finding the very points of contact between them. This is perhaps nowhere more evident than in the opera’s ritualistic scenes of mourning that Kluge foregrounds in relation to Monteverdi’s “Lamento d’Arianna” (Ariadne’s Lament, 1608).[48] It becomes also apparent in the diversity of the Sahel region itself, the point of departure for Bintou Wéré, a Sahel Opera. It is through the exchange that takes place between the performers, coming from thirteen countries in the Sub-Saharan region, that allows each to preserve their own identity, singing the songs in their mother tongues (among them Malinké from Guinea-Bissau, Senegalese Wolof, and Malian Bambara). What the opera scenes also achieve is to draw our attention to the process of cultural mediation itself.

Crucial for this essay, I have argued, is Glissant’s conception of a museum as archipelago. I take the view here that his conceiving of such place, or “point where all the world’s cultures, all the world’s imaginations can meet and hear one another without dispersing or losing themselves,” offers critical inroads into the discussion of the diaspora. Advocating a multiplicity and plurality of voices, Diawara’s carefully constructed filmic essay reverberates in creating such point from which to gain impetus to be in profound contact with the world.

Relatedly, we may consider the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam as a place or point in this “world of differences” that opens for each (artist and) artwork a critical space of belonging, not least through the dialogical exchanges taking place between the works and the collection narratives that are being generated in turn. At the same time, this opening up of such critical space allows each work to preserve its own (hi)story of creation, informed by movement and the social, political, or ecological contexts surrounding it. A fundamentally open meeting place of differences and potentialities for meaning, held together by the notion of relation, or coming into relation that the museum fathoms. This implies not only embracing, but also negotiating differences.

Diawara confronts us with different images, sounds, and concomitant messages to stimulate our capacity for empathy, envisioning forms and gestures of solidarity and collective mourning. At once operatic and cinematic, his film extends beyond spatial and temporal bounds, allowing different genres, different mediums to cohabit, to relate to one another. Just as they in turn may relate to other artworks and productions. By means of montage, Diawara’s aesthetic is one of differentiation in the sense of Glissant’s concept of relation, which moves beyond oppositional discourses.

For this issue, I have introduced within the institution’s realm—by way of this text—Diawara’s essayistic film as a kind of Glissantian Tout-Monde, capable of framing and offering views onto the world; an All-World that accounts for several of the strategies of introducing friction into the workings of institutions. Instead of smoothing out difference, it fights against homogeneity by reintroducing differences, to be understood here “not as that which divide[s] us.” But rather, that “which link[s] us individually and collectively in the Tout-Monde.”[49] And when differences come together, Diawara observes, they can produce unpredictable results.[50] At stake here is the chorus of relations, a shifting aperture onto the world.

About the Author

Anja Isabel Schneider is a curator, writer, and editor. She holds an MA in Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art and an MFA in Curating from Goldsmiths, University of London. From 2015 to 2020 she was a doctoral candidate in Curatorial Research at the Lieven Gevaert Centre, KU Leuven / M HKA, Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp. Currently she is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Castilla-La Mancha and a member of the research group Artea. Research and stage creation, Madrid.

[1] The author acknowledges a postdoctoral research grant for scientific excellence within the framework of the University of Castilla-La Mancha’s own R&D&Innovation Plan, co-financed by the European Social Fund. This research inscribes itself within the research group Artea. Research and stage creation.

[2] The English subtitle reads: “Every diaspora is the passage from unity to multiplicity. This is important in all the movements of the world.” Manthia Diawara, Édouard Glissant: One World in Relation (2009), 48:00 min., K’a Yéléma Productions. French with English subtitles. See also Valérie K. Orlando, “Edouard Glissant: One World in Relation, directed by Manthia Diawara (review),” African Studies Review 59, no. 1 (April 2016): 240.

[3] Statement by Manthia Diawara, used for the promotion of the 34th Bienal São Paulo, accessed November 10, 2022.

[4] Disinterested in my father’s past, I left Germany when I was eighteen and spent two years in Los Angeles, initially as fille au pair to finance my studies, then as a student of Art History and American Literature. Since my time in Los Angeles, and apart from four university semesters pursued in Tübingen, I have been studying, working, and living abroad in several different countries within and outside of Europe.

[5] Tosquelles, for instance, published a text in 1975 in honor of the Martinique-born psychiatrist, philosopher, and writer Frantz Fanon, having hosted Fanon in 1953 at Saint-Alban. Tosquelles’s text “Frantz Fanon en Saint-Alban” focuses on Fanon’s 1953 stay at Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole’s Psychiatric Hospital in 1953, where Fanon did an internship in Tosquelles’ psychiatric department.

[6] Exhibition caption, Francesc Tosquelles: Like a Sewing Machine in a Wheat Field, curated by Carles Guerra and Joana Masó, in the exhibition spaces of the Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, accessed September 27, 2022. I thank Carles Guerra for having introduced me to the work of Tosquelles while preparing the exhibition’s first installment at Les Abattoirs: Musée – FRAC Occitainie, Toulouse (October 14, 2021–March 6, 2022. For the full exhibition tour, see the museum website, accessed November 15, 2022.

[7] Cited in Bernhard Malkmus, “Intermediality and the Topography of Memory in Alexander Kluge,” New German Critique no. 107 (Summer 2009): 245. Such a “head of passion” can be formed, Kluge explains, “for another person, for freedom, for the well-being of one’s own children. When a lot of sensations are united with the entirety of the ability to discriminate in one direction and make reference to a society or other people in the first place, we call this emotion. Emotion, so to say, is the patriotism of sensations.” Alexander Kluge in Alexander Kluge: The Thin Ice of Civilisation. Opera: The Temple of Seriousness (Leipzig: Spector Books, 2019), 64.

[8] One of the subjects proposed in the Call for Research for Stedelijk Studies #12, to be considered in relation to Diaspora. The author thanks Meredith North, Managing Editor of this journal, as well as the editors of this issue for their encouragement and support in writing this text. I am grateful to the two blind anonymous reviewers for their poignant observations and suggestions, which led me to expand the essay, giving attention, among others, to the trauma of migration and to a clearer disclosing of my own subject position.

[9] Manthia Diawara, An Opera of the World (2017), Portugal, Mali, United States, 70:22 min., edited by Kenan Akkawi, was produced by Jürgen Bock (Maumaus / Lumiar Cité) in co-production with the Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development, ZDF/3sat, and the film’s commissioner, documenta 14. The film’s Portuguese premiere was presented in February 2018 at the Cinemateca Portuguesa-Museu do Cinema, Fundação de Serralves, Portugal.

[10] Julia Watson, “Manthia Diawara’s Strategic Ruminations on Migration and the Conundrums of Cinematic Autoethnography,” Cinergie 16 (2019), 14.

[11] Ibid.

[12] AI: African Intelligence (2022), produced by Mamaus/Lumier Cité, commissioned by Gluon, Brussels; Letter from Yene (2022), produced by Maumaus/Lumiar Cité, commissioned by Serpentine, MUBI, and PCAI Polygreen Culture & Art Initiative as part of Serpentine’s Back to Earth project.

[13] Toward a New Baroque of Voices was shown at the 34th Bienal de São Paulo and on view at Amant, Brooklyn, from November 20, 2021 to January 30, 2022, accessed November 12, 2022.

[14] Cf. Watson, “Manthia Diawara’s Strategic Ruminations,” 23.

[15] “Art Against the Grain of ‘Collective Sisyphus’: The Case of Allan Sekula’s Ship of Fools / The Dockers’ Museum (2010–2013)” was a major and long-term research project (2014–2019) jointly pursued by M HKA, Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp, and KU Leuven’s Lieven Gevaert Research Centre for Photography, Art, and Visual Culture, with Hilde Van Gelder as promoter. It was funded by the KU Leuven Research Fund and the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO), with the support of M HKA and the Allan Sekula Studio. The author wishes to thank Jürgen Bock for sharing Diawara’s An Opera of the World with her. Further thanks go to Carlos Alberto Carrilho at Mamaus.

[16] Jürgen Bock, email to the author, February 10, 2021.

[17] Monika Szewczyk, “Manthia Diawara,” in documenta 14: Daybook, eds. Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (Munich, London, New York: Prestel, 2017), accessed June 4, 2022, excerpt available at: https://www.documenta14.de/.

[18] Manthia Diawara, “An Opera of the World: A Remake of Bintou Wéré, a Sahel Opera,” accessed June 3, 2022.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Watson, “Manthia Diawara’s Strategic Ruminations,” 20.

[21] Originally envisioned by Prince Claus of the Netherlands and funded through his culture development trust, An Opera of the World premiered in the open air in Bamako on February 17, 2007. Involving musicians, actors, singers, and dancers, the opera is composed, choreographed, and performed with traditional instruments of Sahelian music by an African cast coming from different countries in the Sub-Saharan region. It is hence performed in different languages, including Wolof (Senegal), Bambara (Mali), Malinké (Guinea-Bissau), and African Creole (Guinea-Bissau).

[22] For a critical reading that raises the question to what extent the original opera may be seen as an “independent ‘African opera,’ or tinted by familiar colonial power asymmetries,” see Sarah Hegenbart, “Decolonising Opera: Interrogating the genre of Opera in the Sahel and other regions in the Global South,” in Musiktheater als Katalysator und Reflexionsagentur für gesellschaftliche Entwicklungsprozesse, eds. Dominik Frank, Ulrike Hartung, Kornelius Paede (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann), 169–196, here 177.

[23] In his film, Diawara does not address how the Sahel Opera came into being. This aspect is mapped in the book publication Bintou Wéré: African Opera by Koulsy Lamko and published by the Prince Claus Fund in 2018. Many thanks to Laura Urbonaviciute at the Prince Claus Fund for sending a copy of the book during the course of revising this essay. Apart from featuring Lamko’s libretto, the book highlights the production process of the Sahel Opera, how it came into being. Since 2003, Lamko has been living in Mexico where he founded a space of refuge for artists and writers promoting African cultures and the African Diaspora.

[24] Manthia Diawara, “An Opera of the World,” accessed June 3, 2022.

[25] Ultimately, Bintou Wéré throws her child to the African side rather than into Spanish territory and dies on the ladder. On the recurrent motif of the ladder, as explained by Wasip Diop, see the following, accessed June 3, 2022.

[26] Marin La Meslée, “Manthia Diawara,” Le Point, translated by the author, accessed June 4, 2022.

[27] Diawara was introduced to Akkawi thanks to one of the filmmakers present at a talk Diawara gave in Greece on Édouard Glissant. See Manthia Diawara, “Public Evening Lecture: Q & A” (Screening of An Opera of the World), The European Graduate School, Saas Fee, August 7, 2018, accessed November 12, 2022.

[28] Alexander Kluge in An Opera of the World, (09:43–10:11).

[29] Akin Adesokan, “An oblique public voice: Revisiting the films of Malian-born author Manthia Diawara,” Africa Is a Country, June 30, 2021, accessed June 9, 2022.

[30] Manthia Diawara, Alexander Kluge, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Steffi Szcerny, “Framing the World: Storytelling through Music and Film,” DLD All Stars, accessed June 8, 2022.

[31] “Why did cinema not become the opera of the 20th century?” Kluge asks in the catalogue to his exhibition The Power of Music, part of the larger project Opera: The Temple of Seriousness held at the kunsthalle weishaupt and Museum Ulm, Germany, 2019–2020, to later stress in an outlook that is future-orientation, the power of music in its capacity to forge relations: “[T]his is how opera of the 21st century will be called film one day.” My translation from the German: “So wird die Oper des 21. Jahrhunderts irgendwann einmal Film heißen.” Kluge, A., and Hauck, S. (2021). Die Wiederbelebung des Scheintoten. Interview mit Alexander Kluge zu Orphea.

[32] As such, Diawara, in line with Kluge, directs his project against the institution of the “sacred” opera house that celebrates the aura of the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Eschewing this notion of totality, Diawara, as some critics foreground, explores opera in terms of movement or (product of) migration. See Szewczyk, “Manthia Diawara,” as excerpted from the documenta 14: Daybook, accessed November 13, 2022. See also Watson, “Manthia Diawara’s Strategic Ruminations,” 21.

[33] “Manthia Diawara, An Opera of the World,” accessed June 3, 2022.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Richard Sennett, who with Kluge is part of the staged “roundtables” in the film, has called our attention to how the message has been divorced from the messenger. “What you have with migration, you appropriate the symbol but not the person. It’s not that the people in my country voted to never listen to another piece of Polish poetry or German opera. They wanted the message, but not the messenger.” (01:10–33).

[36] Watson, “Manthia Diawara’s Strategic Ruminations,” 22.

[37] Hans Ulrich Obrist moderated the interviews with Manthia Diawara and Sylvie Glissant and Genevieve Gallego, among others, together with Asad Raza on the occasion of the exhibition opening Mondialité, curated by Obrist and Raza at Fondation Boghossian, Villa Empain, Brussels, April 18, 2017, accessed November 10, 2022.

[38] La Maison de l’Amérique Latine houses the headquarters of Glissant’s Institut du tout Monde.

[39] See, for instance, the citation of Glissant in Diawara’s film on the crossing/guarding of borders.

[40] How can the celebration of a Glissantian multilingualism, for instance, affect the institution, and with it this very journal?

[41] Glissant had the intention to “present the diversity of the art of both American continents. It was to span from the Mayas to the present: “The basic idea was that I had always wanted to put together a historical and comparative encyclopedia of the arts of the Americas.” According to Glissant, “It is not a recapitulation of something which existed in an obvious way. It is the quest for something we don’t know yet.” Édouard Glissant, cited in Hans Ulrich Obrist, “Le 21ème siècle est Glissant,” in Édouard Glissant & Hans Ulrich Obrist, 100 Notes, 100 Thoughts: Documenta Series 038 (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2012), 5.

[42] Glissant in Obrist, “Le 21ème siècle est Glissant,” 5–6.

[43] Cf. Obrist, “Le 21ème siècle est Glissant,” 4.

[44] Ibid.

[45] In An Opera of the World, Alexander Kluge notes, while in dialogue with Manthia Diawara in his Munich studio, “Now I speak in the voice of my mother to you, but five minutes later it is the voice of my father and you receive it with the voice of your ancestors, you see, I am a chorus of relations and you are another [chorus of relations]. And in opera they could communicate.” (09:20–10:46).

[46] Yet also those of “animate and inanimate objects, visible and invisible forces, the air, the water, the fire, the vegetation, animals and humans.” Manthia Diawara, “Édouard Glissant’s Worldmentality: An Introduction to One World in Relation,” accessed June 5, 2022.

[47] Glissant in Édouard Glissant & Hans Ulrich Obrist, 5.

[48] “Lamento d’Arianna” (2014), from the opera L’Arianna by Claudio Monteverdi, performed by Romina Basso. Furthermore, Diawara selected excerpts from the following: “Triste Apprets,” 2014, from the opera Castor et Pollux (2014) by Jean-Philippe Rameau, performed by Nadine Koulcher and Music Aetena orchestra; “Il Dolce Suono” (1997), from the opera Lucia Di Lammermoor by Gaetano Donizetti, performed by Inva Mula; “Djorolen” (2003) by Oumou Sangaré, performed by Oumou Sangaré; “Salaman” (1999) by Coby Toumani Diabaté, performed Coby Toumani Diabaté and Ballaké Sissoko; and “N’Téri Ni Kaniba” (1975) by Fanta Demba. About the latter, Diawara states: “When I was growing up in Mali in the 1960s, my life was filled with songs in praise of migrants who had replaced epic warriors as the new heroes. These songs, including Dioula, Malamine, Mansane Cisse and Mali Sadio, are still as popular in the hearts of the people of Mali as the modern hits by Salif Keita (Babani) and Fantani Touré (N’Nari). I used one of these heroic migrant songs, “N’Téri Ni Kaniba” (My Friend and Big Love) by Fanta Demba, over the end credits for my film. Demba was the biggest diva of the 1960s and my mother’s favourite singer […]. For a long time, I listened to this song, which reminded me of my mother, as an undying love song. It was only recently, when I was working on the film with my editor in Greece, that I realised that Demba was exhorting men to leave home in order to seek fortunes, because people depended on them to keep on living. In other words, migrants have become the new pillars of drought-affected societies in the Sahel region, the new heroes and the big loves of our lives.” See “Manthia Diawara, An Opera of the World,” accessed June 6, 2022.

[49] Diawara, “Edouard Glissant’s Worldmentality,” accessed June 3, 2022.

[50] Manthia Diawara, “Manthia Diawara in the Archive of Postcolonialism,” interview by Elias Rodriques, The Nation, February 10, 2022, accessed June 7, 2022.