[1] Quoted in Malene Vest Hansen and Kristian Handberg, “Politics of Curating the Contemporary-Modern in the Art Museum,” in Curating the Contemporary in the Art Museum (London: Routledge, 2023), 77.

[2] Geoff Cox and Jacob Lund, The Contemporary Condition: Introductory Thoughts on Contemporaneity & Contemporary Art (London: Sternberg, 2016), 11; Claire Bishop, Radical Museology: or, What’s “Contemporary” in Museums of Contemporary Art? (London: Koenig Books, 2013), 12.

[3] Claire Grace, “1936–2011,” in ICA75 (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 2011), 18.

[4] John Rajchman, “Thinking in Contemporary Art,” lecture as part of FORART series, Institute for Research within Contemporary Art, 2006, transcript, 3.

[5] Dan Karlholm, “Surveying Contemporary Art: Post-War, Postmodern, and Then What?” Art History: Contemporary Perspectives on Method 32, no. 4 (2009): 713; Bishop, Radical Museology, 16.

[6] Karlholm, “Surveying Contemporary Art,” 713.

[7] Knut Ebeling, There Is No Now: An Archaeology of Contemporaneity (London: Sternberg, 2017), 67.

[8] Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “contemporary (adj.), sense 1–4,” September 2023.

[9] On this note, the example I always point to is that the Soviet Union is contemporary with my parents and my parents are contemporary with me; however, as we never existed at the same time, the Soviet Union and I are not contemporaries. Thus, my parents’ contemporary is very different from my own even if we live in the same shared present today.

[10] Amelia Jones, “Introduction: Writing Contemporary Art into History, a Paradox?,” in A Companion to Contemporary Art Since 1945 (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006), 3–4.

[11] Jones, “Introduction,” v–viii.

[12] Throughout this paper I refer to museums that are over one hundred years old as “centenarian” museums; a centenarian is a person who has lived past one hundred years of age. This is not a museological term but rather my own shorthand for referring to century-old contemporary art museums.

[13] The original definition, inscribed in 1946, was replaced in 1974 and again in 2007 (with only slight alterations in between) before being overhauled again in 2022. Bruno Brulon Soares, “Defining the Museum: Challenges and Compromises of the 21st Century,” ICOFOM Study Series 48, no. 2 (2020): 16–32. ICOM currently defines a museum as “a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.” International Council of Museums, “ICOM approves a new museum definition,” ICOM, August 24, 2022.

[14] Hansen and Handberg, “Politics of Curating the Contemporary-Modern,” 2.

[15] In this paper, I adopt the theoretical approach of constructionism as intended in sociology and subsequently adopted by many other fields in the social sciences. The theory of social constructionism has roots in Nietzschean philosophy and was developed by Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann in their seminal 1966 text The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. It posits that individuals and groups who regularly interact in the same sociocultural context will develop collective meanings that become institutionalized over time. Thus, collectively internalized and widely embedded perceptions of reality appear to be objective.

[16] Pedro Erber, “Contemporaneity and Its Discontents,” Diacritics 41, no. 1 (2013): 29.

[17] This notion became especially popular in art historical discourse following Nicolas Bourriaud’s 1998 text Relational Aesthetics.

[18] François Hartog, Regimes of Historicity: Presentism and Experiences of Time, translated by Saskia Brown (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), xv, 201.

[19] Hartog, Regimes of Historicity, 123.

[20] Julia Noordegraaf, Strategies of Display: Museum Presentation in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Visual Culture (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2012), 11–12.

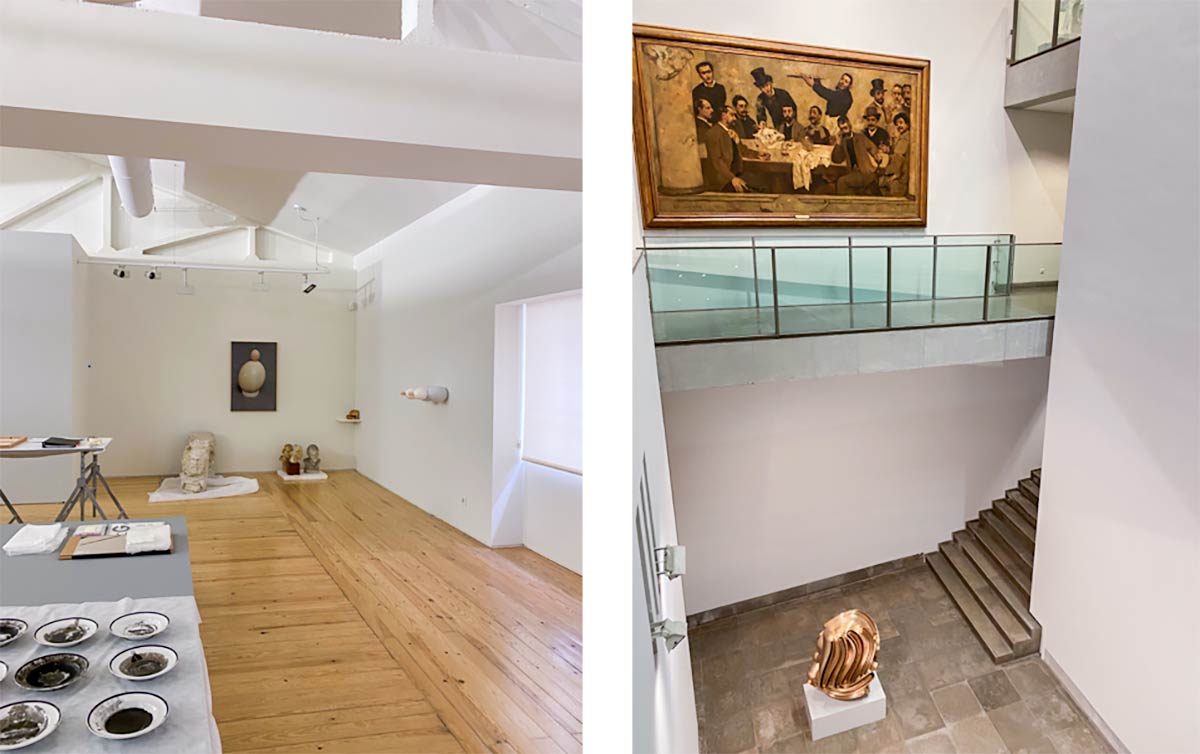

[21] Helena Barranha, “Cien años, un mismo lugar: Museo Nacional de Arte Contemporáneo en el barrio histórico de Chiado (1911–2011),” Arte y Ciudad. Revista De Investigación 3, no. 1 (2013): 291. Translated with Google Translate.

[22] Barranha, “Cien años, un mismo lugar,” 293.

[23] Barranha, “Cien años, un mismo lugar,” 292.

[24] Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea do Chiado, “History,” Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea, accessed December 2, 2024.

[25] Vitor Constâncio, “Forward,” Contemporary Art from Portugal (Art Committee of the European Central Bank & Banco de Portugal, 2002–2003), 8.

[26] Barranha, “Cien años, un mismo lugar,” 302.

[27] Barranha, “Cien años, un mismo lugar,” 302; MNAC director Emília Ferreira, semistructured interview with the author, October 23, 2023.

[28] Ferreira, interview, October 23, 2023.

[29] Ebeling, There Is No Now, 69.

[30] Boris Groys, “Comrades of Time,” e-flux Journal 11 (2009).

[31] Yvette Mutumba and Maurice Rummens, “Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam at 125 Years – Editorial,” Stedelijk Studies Journal 11 (2022); Rixt Hulshoff Pol and Marie Baarspul, Stedelijk in the Pocket (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 2012), 20.

[32] Mutumba and Rummens, “Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam at 125 Years.”

[33] Pol and Baarspul, Stedelijk in the Pocket, 20.

[34] Willem Sandberg quoted in Mary Anna Leigh, “Building the Image of Modern Art: The Rhetoric of Two Museums and the Representation and Canonization of Modern Art (1935–1975); the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Museum of Modern Art in New York” (PhD diss., Leiden University, 2008), 32.

[35] Edy de Wilde quoted in Leigh, “Building the Image of Modern Art,” 33.

[36] Mafalda Spencer, “Willem Sandberg: Warm printing,” Eye 25, no. 7 (1997).

[37] Mutumba and Rummens, “Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam at 125 Years.”

[38] Stefano Collicelli Cagol, “Exhibition History and the Institution as a Medium,” Stedelijk Studies 2 (2015).

[39] Leigh, “Building the Image of Modern Art,” 34.

[40] Leigh, “Building the Image of Modern Art,” 34.

[41] Jelle Bouwhuis, “The Global Turn and the Stedelijk Museum,” in Changing Perspectives: Dealing with Globalisation in the Presentation and Collection of Contemporary Art, ed. Mariska ter Horst (Amsterdam: Kit Publishers, 2012), 157.

[42] Beatrix Ruf et al., “Curating the Stedelijk Collection: A Roundtable Discussion,” Stedelijk Studies 5 (2017).

[43] Susana Simplício, Públicos do Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea—Museu do Chiado (master’s thesis, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, 2010), 12. Translated with Google Translate.

[44] Thomas McEvilley, “Introduction,” in Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 7.

[45] Jan van Adrichem, Adi Martis, and Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Stedelijk Collection Reflections: reflections on the collection of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (Amsterdam: NAi010 Publishers, 2012), 11–14.

[46] Ruf et al., “Curating the Stedelijk Collection.”

[47] Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, “Stedelijk Base Opens 16 December 2017,” Stedelijk, September 13, 2017.

[48] Paul Basu, “The Labyrinthine Aesthetic in Contemporary Museum Design,” in Exhibition Experiments, ed. Sharon MacDonald and Paul Basu (Hoboken: Wiley, 2009), 68.

[49] Terry Smith, Art to Come: Histories of Contemporary Art (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 4.

[50] Basu, “Labyrinthine Aesthetic in Contemporary Museum Design,” 68.

[51] François Hartog, Regimes of Historicity: Presentism and Experiences of Time, trans. Saskia Brown (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015).

[52] This commentary arose from a conversation I had following a visit to the Stedelijk in January 2023 and is supported by Dorothea von Hantelmann, “THE AGENDA OF ART: Politics in Art Today,” in Stedelijk Collection Reflections: Reflections on the Collection of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, ed. Jan van Adrichem, Adi Martis, and Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev (Amsterdam: Nai010, 2012).

[53] Mutumba and Rummens, “Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam at 125 Years.”

[54] Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, “Stedelijk Base Opens 16 December 2017.”

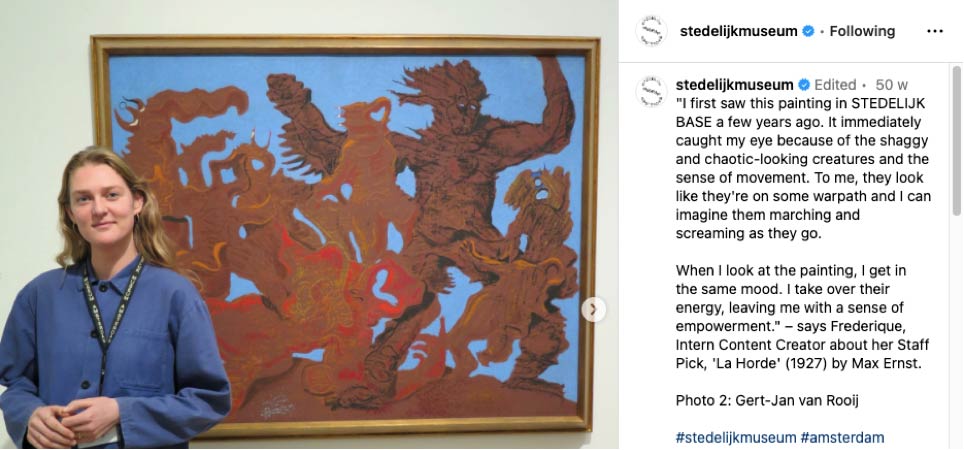

[55] Gwen Parry, “Staff Shares #1,” interview by Valeria Mari, Stedelijk Studies, October 6, 2022.

[56] White Balls on Walls, directed by Sarah Vos (NTR, 2022); see especially 30:12–30:41. Available online: https://www.npodoc.nl/documentaires/2023/06/white-balls.html, accessed December 8, 2024.

[57] Jesús P. Lorente, “From the White Cube to a Critical Museography: The Development of Interrogative, Plural and Subjective Museum Discourses,” in From Museum Critique to the Critical Museum, ed. Piotr Piotrowski and Katarzyna Murawska-Muthesius (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 120–22.

[58] For instance, the audio guide features the voices of curators who provide commentary on the rooms for which they were responsible, while the recurring Instagram segment Staff Picks strives to demystify the faces that work behind the scenes at the museum. Wall text around the museum also frequently contextualizes artistic developments and artworks alongside the Stedelijk’s own institutional history, often accompanied by photographic documentation both in the exhibitions and via social media posts.

[59] Groys, “Comrades of Time.”

[60] Hartog, Regimes of Historicity, 202.

[61] Mieke Bal, Exhibition-ism: Temporal Togetherness (London: Sternberg Press, 2020), 51.

[62] Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea do Chiado, “ARTE PORTUGUESA DO SÉCULO XX (1960–2010),” Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea, 2012.

[63] Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea do Chiado, “ARTE PORTUGUESA DO SÉCULO XX (1960–2010).”

[64] Simplício, Públicos do Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea, 25.

[65] Groys, “Comrades of Time.”